Amalgam Replacement Using a Universal Composite

A simplified solution for the common re-treatment of posterior restorations

Joseph G. Willardsen, DDS

Numerous studies have shown that the clinical diagnosis of secondary caries is the most common diagnosis associated with the need to replace restorations.1 Because this is a type of lesion that patients present with often, a fast and efficient restorative approach is especially needed. When choosing a composite to replace failing amalgam restorations, there are several material properties to consider, including strength, esthetics, and handling. However, many of the composites available today have leveled the playing field, providing nearly identical physical properties regarding those three primary characteristics. With those boxes checked, speed, simplicity, and ease of use rise to the top as deciding characteristics.

The use of a composite material that features a single-shade concept does away with the need to determine and select the correct shade for posterior restorations, which streamlines these procedures and saves time. This case report examines the use of a universal composite in the re-treatment of a posterior tooth with failing amalgam restorations.

Case Report

An adult female patient presented to the practice with three existing amalgam restorations on tooth No. 30 (Figure 1). The amalgam was more than 15 years old, and there were signs of breakdown and recurrent decay surrounding the existing restorations. The clinical objective was to re-treat the patient with conservative direct composite restorations that would mimic the natural tooth structure both esthetically and functionally as well as be easy to place and outlast traditional or other restorative options.

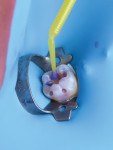

To begin the procedure, tooth No. 30 was isolated with a rubber dam and matrix (Figure 2). Teflon tape was also used to further isolate the tooth and protect against contamination. Once isolated, the old amalgam was removed with a 330 bur, taking special care to remove it safely and in large chunks while preserving as much of the healthy tooth structure as possible (Figure 3). Next, a slow-speed bur was used to remove any recurrent decay, and a caries indicator was applied to establish the caries endpoint (Figure 4).

To help ensure maximum bond strength, a peripheral seal zone was created. In addition, a closer examination for any signs of internal fracture was performed at this stage. With the handpiece set at 10,000 RPM, a round diamond was used to create smooth, rounded internal angles in the preparation.

The cavosurface of the tooth was then cleaned and disinfected (KATANA™ Cleaner, Kuraray Noritake) (Figure 5). The cleaner was applied directly to the tooth as indicated. After the enamel surfaces were cleaned and disinfected, they were selectively etched for 10 to 15 seconds and then rinsed and air-dried to remove all of the remaining etchant (Figure 6).

Once the surfaces were clean, a hybrid layer was created using a universal adhesive (CLEARFIL™ Universal Bond Quick, Kuraray Noritake) that only requires a 3-second scrub to ensure complete adaptation to the hydroxyapatite. This 3-second scrub time is equivalent to the 20-second scrub time of many other brands, which makes it very efficient to use. Next, a thin layer of flowable microhybrid composite (CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ Flow, Kuraray Noritake) was placed and light cured to serve as a liner and base (Figure 7), followed by a 3 mm piece of polyethylene fiber material that was bonded to the floor of the preparation (Figure 8). The polyethylene fiber material was placed to help reduce the C-factor forces that would be created by the inherent shrinkage of the composite restoration as well as to help ensure marginal integrity.2,3

After the polyethylene fiber was cured, approximately 3 mm of the tooth's missing dentin was replaced using a microhybrid composite (CLEARFIL™ AP-X, Kuraray Noritake) applied in small, horizontal layers, each of which was cured before the application of the next in order to assist in reducing C-factor forces. The modulus of elasticity of this composite is equal to that of natural dentin, which allows the restoration to flex, bend, and behave like natural dentin.4 This unique material characteristic helps the restoration mimic the natural tooth structure, ensuring a long-lasting result.

To establish the appropriate occlusal anatomy and color, the restoration was completed using a single-shade universal composite (CLEARFIL MAJESTY ES-2 Universal, Kuraray Noritake). Due to the material's specific level of translucency and the integration of the company's innovative Light Diffusion Technology, it diffuses light in a way that is similar to natural tooth structure. The result is a restoration that blends inconspicuously into the tooth with virtually invisible preparation margins. In addition, this universal composite's ability to match color and adapt to different shades makes the material unique, and its handling makes shaping and forming anatomy extremely simple without the sticking or binding that can be experienced with other composites.

After the universal composite was placed in the area of each individual cusp and cured independently to reduce stress and simplify the cusp shaping process, the occlusal surfaces of the restoration were refined and adjusted with micron articulating paper. At the end of the case, the patient noted that she was pleased with the result and left the office with a functional and esthetic outcome (Figure 9).

Discussion

There are several tactical benefits to using a universal composite. Regarding shade matching, it is easy to become overwhelmed when choosing the right shade. In addition, offices will often stock multiple composites in dozens of different shades. Many of these shades are never used, and they eventually expire only to be replaced by more of the same shades, which eventually go bad as well. This constant replacing of unused composite is a burdensome and unnecessary expense to the dental office. Universal composites eliminate the need to purchase and stock multiple different shades, providing a "go-to" material for most day-to-day direct restorations that also simplifies inventory management.

About the Author

Joseph G. Willardsen, DDS

Cosmetic Dentist

True Dentistry, Esthetic Alliance

Las Vegas, Nevada

References

1. Mjör IA. The reasons for replacement and the age of failed restorations in general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand. 1997;55(1):58-63.

2. El-Mowafy O. Polymerization shrinkage of restorative composite resins. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2004;16(6):452-455.

3. Belli S, Dönmez N, Eskitaşcioğlu G. The effect of c-factor and flowable resin or fiber use at the interface on microtensile bond strength to dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2006;8(4):247-253.

4. Iftikhar N, Devashish, Srivastava B, et al. A comparative evaluation of mechanical properties of four different restorative materials: An in vitro study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019;12(1):47-49.