Using Digital Workflow for Streamlined Processes

Laboratories using modern digital processes maximize dental team cooperation and treatment outcomes

The advantages of the digital workflow are becoming increasingly evident, but are especially apparent with dental implants and other complex cases. Using a laboratory with the capability to digitally design and manufacture both provisional and final restorations, as well as the technology to scan and transmit traditional impressions, enables efficient and effective collaboration. This results in optimal treatment outcomes for patients, as is demonstrated in the two cases presented below.

In both cases, Zenostar® zirconia from Wieland Dental (www.wieland-dental.de), a company of the Ivoclar Vivadent Group (www.ivoclarvivadent.com) was used for the final restorations, which were fabricated by Modern Dental Laboratory USA (www.moderndentalusa.com) with support from Mike Girard, RDT, chief executive officer of Modern Dental USA and Craig Holland, production manager, Modern Dental USA Digital Processing Center.

Case 1

A healthy 59-year-old woman presented with an upper right first bicuspid (tooth No. 5) fractured at the gumline. The tooth was determined to have poor restorative prognosis, and was atraumatically extracted by Maurice Salama, DMD, a dual specialist in periodontics and orthodontics, who then performed immediate implant placement.

The implant site was scanned chairside using the TRIOS® scanner (3Shape Dental, www.3shapedental.com) for CAD/CAM design and fabrication. Using this technology, the laboratory customized a provisional restoration, which Wendy AuClair Clark, DDS, placed to maintain and contour the tissue during healing. When healing was complete, the implant site and tissue contours could then be scanned by Dr. Clark with the TRIOS scanner and electronically transmitted to Modern Dental. The final restoration, a screw-retained zirconia (titanium base) crown with a cutback, was then fabricated by the laboratory team.

At the laboratory, Dr. Clark’s IOS scan file was received electronically and reviewed, as was the digital prescription, which was also verified with the file. The digital models were designed and sent to the 3D printer for fabrication.

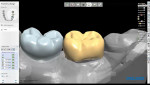

A zirconia-to-titanium screw-retained restoration was designed on a 3Shape system, and the facial cutback was designed digitally (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The designed restoration was then sent to the CAM operator for nesting and milling in the Wieland Select Mill (Wieland Dental). After the milling cycle was completed, the restoration was carefully removed from the zirconia puck. Smoothing of the bars and fine-tuning of the restoration was done in this pre-sintered state, and sintering was performed in a Programat® S1 sintering oven (Ivoclar Vivadent).

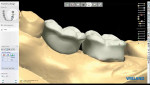

Models were finished and cleaned (Figure 3), and the sintered restoration was seated to the titanium interface and then fitted to the model. The contacts, occlusion, and contours were verified; no adjustments were required.

After the final quality control was performed by the lab, the restoration and printed models were returned to the authors’ office for the porcelain application (Figure 4). The in-house ceramist, Nigel Letren, then layered ceramic over the facial surface of the zirconia substructure for final seating. This allowed for customized esthetics while maintaining the strength of zirconia (Figure 5).

Case 2

A healthy 80-year-old man presented to the authors’ practice complaining of difficulty chewing on the left side of his mouth. In addition to having one missing tooth—the upper left second molar (No. 15)—he was found to have a fractured lower left first molar (No. 19) and a broken single-tooth-supported crown on a lower left second molar (No. 18).

Dr. Salama atraumatically extracted No. 19 and immediately placed an implant there and at the site of the missing tooth No. 15. Traditional impressions of all teeth were made by Dr. Clark and sent to Modern Dental Laboratory.

After the case was received, the impressions and models were carefully reviewed and the prescription was verified with the models. The die for No. 18 was fine trimmed to expose the margin line. A scan abutment was placed on No.15 and scanned into the 3Shape system, where a zirconia-to-titanium screw-retained restoration was digitally designed with a facial cutback.

The designed restoration was sent to the CAM operator for nesting and milling in the Wieland Select Mill. After the cycle was completed, the restoration was carefully removed from the zirconia puck. Smoothing of the bars and fine-tuning of the restoration were done in this pre-sintered state, then sintering was performed in the Programat S1 sintering oven.

After the sintering was completed, the restoration was seated to the titanium interface and then fitted to the model. The contacts, occlusion, and contours were verified; no adjustments were required (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

The restoration was then scanned in with the model as the opposing dentition for the design of teeth No. 18 and No. 19. A scan abutment was placed on No. 19, after which teeth No. 18 and No. 19 were designed (Figure 8). No. 18 was designed as a full-contour zirconia with a facial cutback and No. 19 as a zirconia-to-titanium screw-retained restoration with a facial cutback. Both cutbacks were performed digitally (Figure 9).

The designed restorations were sent to the CAM operator for nesting and milling. After the cycle was completed, the restorations were carefully removed from the zirconia puck. Smoothing of the bars and fine-tuning of the restoration was done in this pre-sintered state, and sintering was performed.

After the sintering was completed, No. 19 was seated to the titanium interface, and No. 18 was seated to the prepared die. Both restorations were seated to the model. The contacts, occlusion, and contours were verified; no adjustments were required.

Final quality control of the case was performed (Figure 10), and all three restorations and the models were returned to the office, where in-house ceramist Nigel Letren layered facial ceramics for the final seating.

Discussion

These restorations were completed using a predictable “textbook” approach plus streamlined communication using digital scans rather than models. The ease of such communication opens up numerous design options not previously available.

A key to the success of these cases was Modern’s ability to design the crowns to maximize their strength. The workflow for these cases was a collaborative effort, with the Modern digital team working closely with the authors’ in-house lab and key ceramist. This enabled the patients to receive strong and esthetic restorations that met their functional and esthetic needs.

About the Author

Wendy AuClair Clark, DDS

Maurice Salama, DMD

Ronald Goldstein, DDS

David Garber, DMD

Private Practice

Atlanta, Georgia

For more information, contact:

Modern Dental Laboratory USA

www.moderndentalusa.com

877-711-8778