Temporary Cement Options

There may not be one provisional cement that is ideal for every situation, but today’s variety of cements offer many benefits.

Robert C. Margeas, DDS

In dentistry, temporary cements are used to temporarily bond provisional restorations, which include inlays, onlays, crowns, bridges, and implants.While there are numerous types of temporary cements, the most common types are eugenol-based, non-eugenol based, and resin based. The newest form of temporary cements in dentistry is glass ionomer. There are several criteria that are important when selecting a temporary cement. Although there may not be a single cement that is ideal for every clinical situation, there are important features that must be included.

- Ease of use

- Good retention to maintain the restoration, but not so good that it cannot be removed

- Adequate working and setting time

- Kind to the soft tissue and pulpal tissue

- Easy clean-up from the provisional

- Easy clean-up of the preparation when the provisional is removed

- No interference with adhesion of the final restoration

- Adequate shelf life

Some of the earliest provisional cements were made from zinc-oxide powder and eugenol liquid. Wallace showed a formula for a predictable zinc-oxide eugenol temporary cement in 1933.1 Eugenol is known to have a sedative effect on the pulp.2 One problem with eugenol-containing cements is that they inhibit the setting reaction of acrylic resins by inhibiting free radical polymerization in the resins used for provisional restorations, and they soften acrylic resins.3

Many manufacturers have introduced eugenol-free cements to address the problem. These cements tend to be a bit more rigid and retain the restoration better and the clean-up is much easier.

Most clinicians will use more than one type of provisional cement. If maximum retention is needed, a resin-based cement may be the material of choice. The problem with some of the resin-based cements is they may bond to composite core materials. This may cause the build-ups to be removed from the tooth when the provisional is removed. If Vaseline is used, this may inhibit the final set of the definitive cement.

In the past, most cements were dispensed as a base and catalyst in squeeze tubes. These were messy, and many times one would be faster than the other, leaving more base then catalyst or vice versa. Convenience packaging has made the use of these cements much easier. They can be automixed, or dispensed simultaneously from one syringe. The double-barreled automixing syringe is the most convenient and gives the most consistent mix. Although it may cost more, it minimizes waste by using only the amount needed.

Case Report

Once the provisional is fabricated, the dentist must make a choice on the type of cement to be used to cement the provisional. The author has been using a non-eugenol–based cement, Zone by DUX Dental (www.duxdental.com), for more than 15 years with excellent results. It is easy to mix and the clean-up is quite easy. The material is dispensed from an automix syringe (Figure 1) into the provisional crown and the temporary is placed on the preparation. Any excess is allowed to set before the material is removed from the restoration (Figure 2). Once the cement has set, it is easily removed from the provisional with a scaler (Figure 3). No petroleum jelly is needed to aid in the clean-up. It is fast and consistently removed with ease (Figure 4).

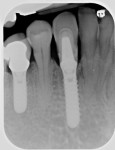

The case illustrated in Figure 5 through Figure 14 involves an implant. The patient’s tooth was removed and the implant was placed (Figure 5). The patient’s natural tooth was hallowed out in order to be used as a provisional restoration (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The natural tooth was relined out of the mouth to fit the solid abutment (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Once the tooth was relined, it was ready for cementation. One trick the author has learned is to remove most of the cement from the restoration out of the mouth before placing it on the abutment. The clinician must work fast if using this technique. The Zone cement was dispensed into the crown (Figure 10) and placed on an analog out of the mouth, and the cement was removed in a few seconds (Figure 11). This was then placed in the mouth on the abutment and any excess cement was removed easily (Figure 12). This tooth has been on the abutment temporarily cemented for more than 6 years (Figure 13). The postoperative radiograph is shown in Figure 14.

Conclusion

While there may not be one single provisional cement that would be ideal for every situation, cements today offer great strength, retention, and ease of use. They are kind to the pulp and clean-up is not a problem. Having used Zone cement for more than 15 years in his clinical practice, the author can say his restorations stay on, but are easily removed when he is ready to seat the final restoration. The material is easily removed from the preparation and there is very little postoperative sensitivity.

References

1. Powers JM. Cements. In: Craig RG, Powers JM. Restorative Dental Materials. 11th edition. Mosby, St. Louis, 2001:593-634.

2. Pashley EL, Tao L, Pashley DH. The sealing properties of temporary filling materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1988;60(3):292-297.

3. Gegauff AG, Rosenstiel SF. Effect of provisional luting agents on provisional resin additions. Quintessence Int. 1987;18(12):841-845.

About the Author

Robert C. Margeas, DDS

Private Practice

Des Moines, Iowa