Basics of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Margaret I. Scarlett, DMD

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). This virus is highly variable and mutates easily. HIV-1 is the most commonly reported strain of the virus in the United States and around the world; HIV-2 is found primarily in West Africa and rarely reported in this country.

The two types of HIV are both transmitted in the same ways, and both cause similar clinical symptoms. The main differences are that HIV-2 appears to be transmitted less easily than HIV-1 and to take longer from initial infection to the development of symptoms.

HIV-1 viruses are subdivided further into groups, based on genetic similarities, with Group M (the “major” group) being the most common. Group M is further classified into at least 10 subtypes, which will not be discussed in further detail here; the other two groups, O and N, appear to be restricted to specific areas in Africa.

What is AIDS?

As stated above, AIDS is an acronym for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Here is the definition of each term:

Acquired—means that the illness comes from contact with a disease-causing agent (HIV) rather than being inherited genetically from a parent.1

Immunodeficiency—means it produces a weakened immune system, leaving the patient more vulnerable to illness than people with healthy immune systems.1

Syndrome—means it is a group of symptoms that, together, are indicative of a disease. People who have AIDS usually develop a number of infections or cancers, and the number of specific cells in their immune systems usually decreases.1

Only a physician can make a diagnosis of AIDS after completing specific clinical or laboratory tests that show the patient’s illness meets the current Public Health Service (PHS) definition of AIDS.2 The name “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)” was first used by public health officials in 1982 to describe cases in previously healthy people who developed multiple conditions, including opportunistic infections, Kaposi’s sarcoma (a kind of cancer), and Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia. AIDS surveillance (formal tracking of new and existing cases and attributable deaths) began that year in the United States.3

What is the Current Definition of AIDS?

In response to emerging discoveries about AIDS over time, the PHS has revised the AIDS surveillance case definition (physical and laboratory findings that make up an AIDS case) a number of times. The current definition was adopted in 1993, when it was expanded to recognize the importance of immunologic testing (CD4+ T-cell counts) and a broader range of related illnesses. The result was an immediate “surge” in the number of reported cases in 1993 when cases that previously did not meet the definition were added.1,4

The current AIDS case definition includes all cases in HIV-infected persons who have less than 200 CD4+ T-lymphocytes/µL, or a CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of less than 14. Three clinical conditions also were added in 1993—pulmonary tuberculosis, recurrent pneumonia, and invasive cervical cancer—and the 23 clinical conditions in the AIDS surveillance case definition published in 1987 were retained.5

What Do We Know About the Origins of HIV and the Beginning of the US AIDS Epidemic?

Researchers believe that HIV-1 originated in a subspecies of chimpanzees native to west equatorial Africa and entered the human population when hunters killed the chimpanzees and somehow were exposed to their infected blood.6

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HIV-1 was first identified in humans in a blood sample collected in 1959 from a man in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. No one knows how he became infected. Scientists who conducted genetic analyses of this blood sample concluded that HIV-1 probably originated as a single virus in the late 1940s or early 1950s and began spreading silently in the African population.6

The virus was not recognized in the United States until the early 1980s, but scientists now know that it had to have been introduced here at least a decade before. Between 1979 and 1981, physicians in Los Angeles and New York were seeing rare types of pneumonia, cancer, and other illnesses among some male patients who had sex with other men. The conditions being reported by these physicians were conditions they did not normally see in patients with healthy immune systems.6

Scientists discovered in 1983 that these illnesses were the result of a viral infection, and an international scientific committee first named the virus HTLV-III/LAV (human T-cell lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus). Later, the name was changed to human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV.6

Scientific understanding of HIV and AIDS evolved rapidly following the discovery of the virus. Early on, scientists identified transmission modes and groups at highest risk of becoming infected. They learned that about half of those infected with HIV would progress to AIDS in approximately 10 years. However, they also discovered that this time period was highly variable and depended on the state of the patient’s overall health and other health-related factors (for example, whether or not they ate healthy foods, exercised regularly, got enough sleep, or took the right drugs early in infection).4,7

The progression time between HIV infection and the development of AIDS has been extended dramatically since the introduction of powerful new antiviral drugs in 1996. Other recently discovered medical treatments can prevent or cure some of the infections and other illnesses associated with AIDS, but to date nothing has been found that can cure AIDS itself.7

What are the Symptoms of HIV Infection?

A blood test is the only way to determine conclusively that a person is infected with HIV. Many symptoms of HIV infection are the same as for other diseases or conditions, and most people who are infected with HIV do not have any symptoms for many years.8

The following may be warning signs of HIV infection:

- Rapid weight loss

- Dry cough

- Recurring fever or profuse night sweats

- Profound and unexplained fatigue

- Swollen lymph glands in the armpits, groin, or neck

- Diarrhea that lasts for more than 1 week

- White spots or unusual blemishes on the tongue, in the mouth, or in the throat

- Pneumonia

- Red, brown, pink, or purplish blotches on or under the skin or inside the mouth, nose, or eyelids

- Memory loss, depression, and other neurologic disorders

No one should assume they are infected if any of these symptoms are present. Again, the only way to determine whether a person is infected is to be tested for HIV infection.

Symptoms also are not conclusive evidence that a person has AIDS. AIDS is a medical diagnosis made by a physician based on specific criteria established by the CDC. For more information, refer to the “1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults.”2

What is the Current Status of the HIV Epidemic in the United States?

New estimates released in the Journal of the American Medical Association in August 2008 show that in 2006, an estimated 56,300 new HIV infections occurred. This estimate is much higher than the previous estimate of 40,000 annual new infections.9 While the new estimates are much higher than the old ones, a separate CDC historical trend analysis published as part of this study suggested that the annual number of new infections was never as low as the old estimates of 40,000 new infections annually. Rather it has been roughly stable since the late 1990s (with estimates ranging between 55,000 and 58,500 during the three most recent time periods analyzed).10

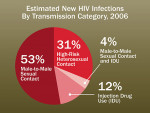

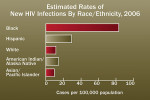

The new estimates show that gay and bisexual men of all races and ethnicities and African-American men and women are the groups most affected by HIV. In 2006, 53% of all new infections occurred in gay and bisexual men (Figure 1). African Americans, while comprising 13% of the US population, accounted for 45% of the new HIV infections in 2006.

The findings indicate that HIV incidence has been increasing steadily among gay and bisexual men since the early 1990s. The analysis also found that new infections among African Americans are at a higher level than any other racial or ethnic group (Figure 2), though they have been roughly stable, with some fluctuations, since the early 1990s. These numbers indicate that the US HIV/AIDS epidemic is far from over. Even though better treatments have led to an increase in the number of people in the United States who are living with HIV/AIDS, that number is still about half a million.11

HIV Transmission

HIV is spread in a limited number of ways:

- Through sexual contact with an infected person. Heterosexual contact, male-to-male sexual contact, and female-to-female sexual contact all present varying degrees of risk for HIV infection. Evidence suggests that the risk from oral sex is less than that from unprotected anal or vaginal sex, but the exact degree of risk from oral sex is not known. Virus from an infected partner may enter the partner’s body through the lining of the urethra (the opening at the tip of the penis), the lining of the vagina or cervix, the lining of the anus, or directly through small cuts or open sores, such as in the mouth. If a person has HIV, their blood, semen, pre-seminal fluid, or vaginal fluid may contain the the virus. Cells lining the mouth of the person performing oral sex may allow HIV to enter their body. The risk of HIV transmission is greater if the person performing oral sex has cuts or sores around or in their mouth or throat, if the person receiving oral sex ejaculates in the mouth of the person performing oral sex, or if the person receiving oral sex has another sexually transmitted disease (STD).12

- By sharing needles and/or syringes (primarily for drug injection) with someone who is infected. Sharing needles is a highly efficient way in which to transmit infection. In addition, sharing of drug paraphernalia, such as cooking equipment, cotton balls soaked in blood, and other items may facilitate the transmission of HIV.12

- Through transfusions of infected blood or blood-clotting factors. This mainly occurred in the United States before the routine screening of donated blood and blood-clotting factors began in 1985. It is now extremely rare in countries where blood is screened for HIV antibodies.12

- Babies born to HIV-infected mothers may become infected before or during birth or through breast-feeding after birth. Again, this has become much less common as HIV screening rates have increased among pregnant women, and women found to be infected and their newborns are treated with antiretroviral therapies.12,13

Healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, dentists, phlebotomists, etc) can become infected with HIV if they are stuck with a needle containing HIV-infected blood. They also can become infected if a patient’s infected blood comes into contact with an open cut on the healthcare worker’s skin or gets into a mucous membrane such as the eyes or inside of the nose. These types of transmissions, however, are rare—only 57 such cases were reported in the United States from the beginning of the epidemic through 2004.

Patients of infected healthcare workers are at extremely low risk of being infected by their caregivers. Only once has such a case been documented in the United States, and this involved HIV transmission to six patients from a single infected dentist. In that case, the route of transmission from the dentist to his patients was never conclusively determined. More than 22,000 patients of 63 other HIV-infected physicians, surgeons, and dentists have been investigated, and no other instances of this type of transmission have been found.11,14

The United States has a national sentinel system in place that was designed to detect any new transmission modes that might arise. State and local health departments, with help and laboratory support from federal researchers, vigorously investigate all cases suggesting a new or previously unknown transmission route; to date, no scientific evidence has been found to support these claims, and no transmission modes besides those identified previously have been recorded.11

Common Misperceptions About HIV Transmission

Some people are concerned that an individual could become infected from contact with HIV on an environmental surface. However, scientists have learned that HIV does not survive well in the environment, and the chance of becoming infected from any kind of environmental transmission is remote.15 Laboratory studies designed to obtain data on the survival of HIV outside its living host have required the use of very high concentrations—higher than those usually found in blood, semen, vaginal fluid, breast milk, saliva, or tears—of laboratory-grown virus.14 Although this laboratory-grown HIV has been kept alive for a period of days or weeks under precisely controlled conditions, studies have shown that the amount of infectious virus is reduced as it dries by 90% to 99% within just a few hours.14 Because the HIV concentrations used in these studies were much higher than those actually found in any body fluid, the drying process virtually eliminates the theoretical risk of environmental transmission. In fact, no such transmissions have ever been documented. Also, because HIV is unable to reproduce outside its living host (except under laboratory conditions), it does not spread or maintain infectiousness outside its host.14

Kissing

Closed-mouth or “social” kissing, such as on the cheek, is not a risk for transmission of HIV. Open-mouth (“French”) kissing may present a risk because of the potential for contact with blood during the kiss. Even though the risk of acquiring HIV during open-mouth kissing is believed to be very low, experts recommend against engaging in this activity with a person known to be infected. Public health officials have investigated only one case of HIV infection that may be attributed to contact with blood during open-mouth kissing.14

Biting

In 1997, researchers at the CDC published findings from a state health department investigation of possible blood-to-blood transmission of HIV from a human bite. A few other reports in the medical literature have suggested that HIV may have been transmitted through biting—each of these incidents involved severe trauma, extensive tissue damage, and blood. There also have been numerous reports of bites that did not result in HIV infection.14

Saliva, Tears, and Sweat

Very small amounts of HIV have been found in the saliva and tears of some AIDS patients. However, finding a small amount of HIV in a body fluid does not necessarily mean that HIV can be transmitted by that body fluid. HIV has not been found in the sweat of HIV-infected persons. HIV transmission through contact with saliva, tears, or sweat has never been documented.14

Prevention in Healthcare Settings

Healthcare personnel are at risk for occupational exposure to HIV and other bloodborne pathogens, such as hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus. Healthcare workers may be exposed (1) through needle sticks or cuts from other sharp instruments contaminated with an infected patient’s blood; or (2) if infected blood gets into the healthcare worker’s eye, the inside of the nose or mouth (mucous membranes), or into a cut or abrasion in the skin. The number of infected individuals in the patient population and the type and number of blood contacts both affect the overall risk for occupational exposure. Most exposures do not result in infection—only 57 AIDS cases resulting from occupational HIV exposure have been recorded since the beginning of the epidemic.1

To best protect themselves from infection, healthcare workers should assume that the blood and other body fluids from all patients could be infectious. Therefore, the following infection control precautions should be observed at all times:

- Routinely using barriers (such as gloves and/or goggles) when anticipating contact with blood or body fluids.

- Washing hands and other skin surfaces immediately after contact with blood or body fluids.

- Careful handling and disposing of sharp instruments during and after use.

During the past two decades, technologic advances and the development of safety devices have reduced the risk of being stuck by a needle. Safety devices may reduce the risk for HIV exposure if used correctly. Many percutaneous injuries are related to sharps disposal, but safer designs for disposal containers, along with better placement of containers, have led to reductions in the number of such injuries.12-20

Although preventing occupational exposures is the most important strategy for reducing the risk of occupational HIV transmission, postexposure therapies are available and may be used when exposures do occur. The CDC has issued guidelines for the management of healthcare worker exposures to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) using antiretroviral therapies. These guidelines discuss considerations for helping decide whether healthcare personnel should receive PEP and what type of PEP regimen should be used. They also discuss special circumstances, such as a delayed exposure report, unknown source person, pregnancy in the exposed person, resistance of the source virus to antiviral agents, and toxicity of PEP regimens.

Generally, the CDC recommends that a basic 4-week, two-drug (there are several options) regimen be used for most HIV exposures that warrant PEP. For HIV exposures that pose a higher risk for transmission (based on the infection status of the source and the type of exposure), a three-drug regimen may be recommended. However, any occupational exposure should be considered an urgent medical issue, with referral to a physician who treats infectious diseases.

Although the transmission of HIV to patients from HIV-infected healthcare workers has been documented in healthcare settings, such transmission is rare. The use of proper sterilization and disinfection procedures protects patients and clients and is required in all healthcare settings. Dental patients can be treated safely in a dental office following universal precautions. Universal precautions, oral findings of AIDS, current HIV treatments, and dental treatment issues for persons with HIV will be detailed in Part 2 of this series: “Treatment Issues for Dental Patients with HIV/AIDS.” Updated treatment regimens and evidence based reviews will be addressed.22

Conclusion

HIV likely entered the human population in the United States in the 1970s and was first identified as the cause of AIDS in 1983. AIDS is characterized by the development of a number of opportunistic infections, some cancers, and a weakening of the immune system. A laboratory blood test is the only way to establish conclusively whether the patient is infected with HIV, and only a physician can make a diagnosis of AIDS. Oral healthcare workers can protect themselves from HIV by using universal precautions.

References

1. Smith RA. Encyclopedia of AIDS. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers; 1998:1-601.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-17):1-19.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia among homosexual men—New York City and California. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1981;30(25):305-308.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for national human immunodeficiency virus case surveillance, including monitoring for human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-13):1-31.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; AIDS Program, Center for Infectious Diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1987;36(Suppl 1):1S-15S.

6. CDC. Fact Sheet. Where did HIV come from? https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/qa/qa3.htm. Accessed December 22, 2008.

7. Hammer SM, Eron JJ Jr, Reiss P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel. JAMA. 2008;300(5):555-570.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR14): 1-17.

9. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV incidence. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/incidence.htm. Accessed Aug 8, 2008.

11. Do AN, Ciesielski A, Metler RP, et al. Occupationally acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: national case surveillance data during 20 years of the HIV epidemic in the United States. Infect Contr Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(2): 86-96.

12. CDC Fact Sheet. Preventing the Sexual Transmission of HIV. What You Should Know about Oral Sex. December 2000. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/Factsheets/pdf/oralsex.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2008.

13. CDC Fact Sheet. HIV and AIDS: Are You At Risk. July 2007. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/brochures/at-risk.htm. Accessed December 22, 2008.

14. Ciesielski C, Marianos D, Ou CY, et al. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in a dental practice. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(10):798-805.

15. CDC Fact Sheets. HIV and Its Transmission. July 1999. Accessed December 22, 2008.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in health-care settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1987;36(Suppl 2):1S-18S.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transmission of HIV possibly associated with exposure of mucous membrane to contaminated blood. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46(27):620-623.

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: universal precautions for prevention of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and other bloodborne pathogens in health-care settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1988;37(24):377-388.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Nosocomial Infections: Guideline for Handwashing and Hospital Environmental Control. Atlanta, GA: Public Health Service; 1985:1-20.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for prevention of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus to health-care and public-safety workers [published erratum appears in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38(43):746]. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 1989;38(Suppl 6): 1-37.

21. CDC Fact Sheet. Preventing Occupational Transmission of HIV. February 2002. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/Factsheets/hcwprev.htm. Accessed December 22, 2008.

22. Bonito AJ, Patton LL, Shugars DA, et al. Management of Dental Patients Who are HIV-Positive. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 37 (Contract 290-97-0011 to the Research Triangle Institute-University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Evidence-based Practice Center). AHRQ Publication No. 01-E042. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002.

Web and Other Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): www.cdc.gov/hiv

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (for information on HIV testing): www.fda.gov/cber/products/testkits.htm

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), HIV/AIDS Bureau: www.hab.hrsa.gov

- National HIV and STD Testing Resources: www.hivtest.org or call 24 hours/day: 800-CDC-INFO (232-4636)

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases: www.niaid.nih.gov/publications/aids.htm

About the Author

Margaret I. Scarlett, DMD

President

Scarlett Consulting International

Atlanta, Georgia