Infectious Disease Update

What you must know about hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis to keep you and your patients safe

Diseases may be carried by organisms that are found in contaminated food or water, insects, and animals; in the particles released when an infected person coughs or sneezes; and through bodily fluids, secretions and excretions from an infected person. Even bacteria colonized on a person’s skin can transmit disease. Incubation periods can vary widely. In some cases, diseases can remain latent in a person for years and become activated when the immune system is vulnerable (such as with tuberculosis and herpes zoster). Because of the increased potential for exposure to bodily fluids, healthcare delivery carries specific risks for disease transmission from patient to clinician, patient to patient, and clinician to patient.

Most exposures to infectious microorganisms do not result in the transmission of infectious diseases partly because a person’s vaccinations and immune system protect against contracting illnesses. In addition, not all diseases are equally virulent, and the frequency and degree of exposure also play a role in whether a person contracts an infection. This article will provide updated information on some of the most common infectious diseases that are concern to dental healthcare providers (DHCPs).

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) may be transmitted through contact with bodily fluids from a person with either an active or chronic HBV infection. This is particularly significant in healthcare because it is known that transmission may occur in dental care settings from patient to healthcare worker, healthcare worker to patient, and patient to patient.1,2 Transmissions may be due to percutaneous injury such as needle sticks, mucous membrane or non-intact skin contact with contaminated bodily fluids, improper sterilization practices, mishandling of multi-dose medication vials, and contaminated medical or dental equipment.

Largely due to widespread adoption of the hepatitis B vaccine, a dramatic decrease in new cases of hepatitis B in the past several decades has occurred—an estimated 81% decline between 1991 and 2009.3 Despite this, chronic HBV remains a major public health challenge, with 700,000 to 1.4 million persons in the United States chronically infected and capable of transmitting HBV.4

HBV may be spread by having unprotected sex with an infected individual, by an infected mother to her infant at birth, by contact with the blood or open sores of an infected person, through needle sticks and other contaminated exposures, and by sharing household items such as razors and toothbrushes with an infected person. The virus can survive for 7 days outside the body and still transmit infection. The use of proper disinfection and sterilization procedures and appropriate personal protective attire is important for preventing the transmission of HBV in the dental office setting.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the most common chronic bloodborne infection in the United States, with an estimated 3.2 million people chronically infected. Chronic infection means that the virus is actively replicating in the liver and circulates in the blood and other bodily fluids. Infected individuals may transmit HCV. The most common means of transmission in the United States is through illegal-injection drug use. An approximated one-third of young injecting drug users (ages 18 to 30 years) are HCV infected.5 Other means of transmission include blood and blood product transfusions and organ transplantation. Rarely, HCV may be transmitted sexually or by sharing personal items contaminated with blood. Rare outbreaks associated with healthcare have also been documented.6 Blood screening became available in 1992, resulting in a significant decline in the number of cases associated with transfusions and transplantations, although cases do occur rarely. Sharps injuries in healthcare have also resulted in HCV transmission, although transmission via this route is less likely than it is with HBV. Infants born to infected mothers may also contract HCV during birth.5

Tuberculosis

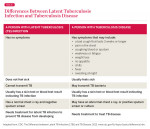

Although not a bloodborne disease, tuberculosis (TB) is of concern in healthcare settings, and DHCPs should know the signs, symptoms, and necessary steps for encountering a patient known or suspected of having an active infection. Two TB-related conditions exist: latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and active infection (Table 1). Infection may occur when inhaling particles released when someone with active TB coughs, sneezes, speaks, or sings. These airborne particles are called droplet nuclei. Most people infected with TB will never develop active infections but will have LTBI. Persons with LTBI may have positive TB skin test results but cannot transmit TB and are not symptomatic for TB.

Only patients with active TB can transmit the disease. Most people with active TB will have specific symptoms, including productive and persistent cough, bloody sputum, night sweats, weight loss, fever, anorexia, or a combination of these.7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has suggested that all healthcare settings be divided into three categories depending on the risk for occupational exposure to TB: low risk, medium risk, and facilities with ongoing transmission risk. Most dental settings are categorized as low risk.7 Healthcare settings in the low-risk category should still have a TB control program as part of their overall infection-control programs. Precautions should include initial baseline TB skin testing, screening for patients possibly symptomatic for TB on the health history forms, and the use of transmission-based precautions (or referral to a facility capable of providing airborne precautions) as described later in this article.

Standard Precautions

In addition to the routine precautions such as vaccination and cough etiquette that may help prevent disease transmission in healthcare settings, standard precautions are used. These are a set of infection control strategies that, when appropriately applied, reduce the risk for infection among patients and clinicians. Standard precautions apply to contact with blood and all bodily fluids, excretions, or secretions whether or not they contain blood.8 Standard precautions include the use of protective attire such as gloves, masks, gowns and protective eyewear; disinfection and sterilization processes; hand hygiene; safe injection practices; and safe handling of potentially infectious materials.9

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, certain situations or infections require the use of transmission-based precautions. These fall into three major categories: contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. These precautions are usually not feasible in outpatient settings. Depending on the situation, it may be necessary to delay non-emergency dental treatment for patients with certain illnesses.9

Diseases that require contact precautions are those that would be unlikely to be encountered in a dental setting and are transmitted via contact with a person’s stool containing Clostridium difficile, norovirus, rotavirus, and others.10

Droplet precautions apply to patients with respiratory viruses, such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and pertussis. Such precautions consist mainly of isolation of the patient from others and the use of masks and other personal protective equipment by healthcare providers.10 With respiratory illnesses, it is more prudent in a dental office to reschedule a patient’s appointment than attempt to follow droplet precautions.

Diseases that spread by the airborne route, such as chicken pox (until lesions are crusted over), TB, measles, or herpes zoster (until lesions are crusted over), require airborne precautions in addition to standard precautions.10 The treatment for patients with these active or incubating diseases should only be performed in a facility equipped with an airborne infection isolation room. If no immediate treatment is needed, the patient should be asked to return when symptoms have dissipated. If immediate treatment is needed, the patient should be transferred to a facility with an airborne-infection isolation room.8

Work Restrictions

While much of the focus of infection control in healthcare is on preventing transmission from patient to healthcare worker and patient to patient, it is also important to know when an ill healthcare worker may pose a risk for patients. For some illnesses, DHCPs should refrain from patient care only while symptomatic. For others, such as chicken pox, it may be necessary to restrict contact during the potential incubation period. Click here to see Table 2, which outlines outlines the CDC recommendations for work restrictions for healthcare workers. These restrictions are necessary because of the potential risk for infection, particularly for patients who have underlying medical conditions or are particularly vulnerable to infection (eg, people with diabetes, chemotherapy patients, persons with HIV).

Conclusion

Although infectious diseases are common, understanding the mode of transmission for diseases and implementing sound infection-control practices will make the practice of dentistry safe for the dental team and patients. Numerous resources exist that will assist dental assistants in remaining current on infection-control recommendations. Some resources specific to dental infection control and safety are listed on the next page.

About the Author

Eve Cuny, MS

Associate Professor, Dental Practice

Director, Environmental Health and Safety

University of the Pacific

Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry

San Francisco, California

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Hepatitis B and C Outbreaks Reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2008-2012. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/healthcarehepoutbreaktable.htm. Accessed August 21, 2013.

2. Redd JT, Baumbach J, Kohn W, Nainan O, Khristova M, Williams I. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007; 195(9):1311–1314.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B Information for Health Professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm#overview. Accessed August 21, 2013.

4. Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States in the era of vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(2):192-201.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C Information for Health Professionals. 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#b1. Accessed August 29, 2013.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Hepatitis B and C Outbreaks Reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2008-2012. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/healthcareoutbreaktable.htm. Accessed August 29, 2013.

7. Cleveland JL, Robison VA, Panlilio AL. Tuberculosis epidemiology, diagnosis and infection control recommendations for dental settings: an update on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(9):1092-1099.

8. Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM; for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR17):1-61.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guide to Infection Prevention for Outpatient Settings: Minimum Expectations for Safe Care. Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/guidelines/standatds-of-ambulatory-care-7-2011.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2013.

10. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, for the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/isolation2007.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2013.