Saliva Diagnostics: “Build It and They Will Come”

What impact would a profession of 157,000 dentists and 174,000 hygienists have if they were actively engaged in chairside screening of medical conditions?

In an article published in 2010 in the Journal of the American Dental Association, Greenberg et al surveyed 1,945 practicing dentists and asked them if they were willing to collect a sample of saliva and submit the sample for a diagnostic evaluation.1 Eighty-seven percent of the respondents were receptive to integrating this procedure into their clinical practice. The surprising element was the overwhelming responsiveness despite the fact that there is no risk assessment or diagnostic test available at this time. One interpretation is that when the science and the technologies are able to clinically enable salivary diagnostics, the practicing community will embrace it: build it and they will come.

The past decade has seen significant advances in the basic and translational sciences of saliva, largely due to the visionary investments of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) to decipher and catalog the human salivary proteome and develop saliva-based point-of-care technologies. What awaits is the clinical maturation of these basic and translational ou comes into clinical product developments that can benefit the very patients we wish to serve in the first place. This article presents the current status of the translational posture of saliva and its constituent biomarkers for the detection of oral and systemic diseases.

Salivary Biomarker Changes in Systemic Disease

While there is little doubt that saliva testing (risk assessment) for oral diseases such as oral cancer, periodontal diseases, caries, dry mouth, and salivary gland diseases will likely be a clinical reality in the next 3 to 5 years, the translational crossover of salivary biomarkers for systemic disease detection is less certain. The lack of a mechanistic rationale to demonstrate that salivary biomarkers change resultant of distal disease has been hampering scientific and biological acceptance. To address these mechanistic gaps, rodent models have been used to unravel the scientific underpinning of distal disease pathogenesis and salivary biomarker development. A working model currently being tested is one of tumor-shed microvesicular structures known as exosomes, which are 30 nm to 100 nm in size, can shuttle tumor-specific contents to different parts of the body including the salivary glands, leading to the onset and development of specific biomarkers in saliva.2 The research community envisions that when the scientific underpinnings of salivary diagnostics credibly reveals itself for systemic diseases, the acceptance of salivary biomarkers for translational and clinical applications will be significantly increased. An exciting moment in dentistry awaits.

Clinical Development of Salivary Biomarkers

While the scientific rationale of salivary biomarkers reflecting systemic diseases awaits scientific evaluation, the translational and clinical development of salivary biomarkers for systemic disease detection has been in full throttle for the past few years. Most noted are the efforts to develop salivary biomarkers for molecular oncology detection, including cancers of the breast,3 pancreas,4 lung,5 and ovaries.6 Significant efforts were invested in demonstrating the value of blood-based markers in saliva for detection of myocardial infarction (heart attack)7 as well as the de novo development of salivary biomarkers to detect Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with sicca symptoms (dry eyes, dry mouth).8 These developed salivary biomarkers can be advanced on the clinical validation path toward pivotal and definitive validation by the Food and Drug Administration. The eventual convergence between clinical validation and mechanistic revelation of distal diseases reflected in saliva will fully credential this secretion for molecular diagnostics.

Point-of-Care Technology

The vision of the NIDCR toward translational and clinical maturation of salivary diagnostics includes a parallel and timely development of point-of-care technology platforms that can enable the measurements of multiple salivary constituent targets for early detection and/or risk-assessment applications. Figure 1 illustrates the UCLA-developed platform, the Oral Fluid NanoSensor Test (OFNASET). This is a robust, fully automated, real-time, low-cost, truly multiplex point-of-care platform that can concurrently detect salivary protein, nucleic acids (eg, DNA and RNA), and microbiome biomarkers. The marriage of discriminatory salivary-biomarker development with saliva-optimized point-of-care technologies is the vision that is awaiting clinical maturation.

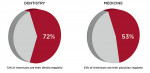

Greenberg’s article provided a telltale sign of the receptiveness of the dental profession for saliva-based screening/risk-assessment technologies. Factoring in that ~20% Americans see their dentists more regularly than their physicians, and that a dentist has, on average, a patient roster of ~2,000, the 20% differential between dentist and physician visits can translate into significant opportunities for dentists to engage in the early detection of life-threatening conditions (Figure 2). When salivary diagnostics is fully integrated into dentistry, it presents an opportunity to advance dentistry into primary healthcare.

What impact would a profession of 157,000 dentists and 174,000 hygienists have if they were actively engaged in chairside screening of medical conditions? Studies have indicated that oral healthcare professionals using well-validated, safe, simple, and well-recognized screening tools—including finger-stick blood—can successfully identify patients who are at risk but yet unaware of developing such medical conditions as coronary heart disease and diabetes. Data extrapolated from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggested that chairside medical screening by oral healthcare professionals for the initial identification of patients at risk for developing a cardiovascular event, such as angina or a heart attack, would be highly beneficial.9 According to the data, 18% of patients at increased risk of developing a cardiovascular event within 10 years—yet unaware of their increased risk—could be identified through medical screening in a dental setting. An inner-city clinic-based study in which oral healthcare professionals conducted chairside medical screening for coronary heart disease identified 17% of asymptomatic dental patients with an increased risk of disease.10 A preliminary study assessed the diagnostic yield among 200 dental patients with no history of cardiovascular disease who screened positive for increased risk of disease and were referred for medical follow-up.11 It reported that 75% (9 out of 12).completed the referral visit and of those, six received medical intervention.11 An interesting observation from this study is that that no women were identified as having a need for cardiovascular disease prevention. Thus, a targeted screening protocol of only men would have discovered a 12% prevalence of all men who were unaware of, yet found to be at risk for, coronary heart disease.11

Conclusion

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s investment efforts over the past 10 years have led to the alignment of important stakeholders that are necessary to be in place to advance the basic, translational, and clinical sciences to mature salivary diagnostics into becoming a clinical reality. Critical steps to acceptance include the investments by the NIH (and particularly the NIDCR) in the foundational science; the academic community’s.commitment to develop impactful scientific and translational ou comes employing the salivary diagnostic toolboxes of biomarkers and point-of-care technologies; and corporate partnerships’ readiness to license the technologies to develop them for regulatory approval and eventual product development (Figure 3). Advocacy by organized dentistry, particularly the American Dental Association, and the need to engage the payors in order to render saliva testing reimbursable are all fundamentally critical, essential, and pivotal to ensure that these developed sciences can be translated into clinical realities.

References

1. Greenberg BL, Glick M, Frantsve-Hawley J, Kantor ML. Dentists’ attitudes toward chairside screening for medical conditions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(1):52-62.

2. Lau M, Wong DTW. Breast cancer exosome-like microvesicles and salivary gland cells interplay alters salivary gland cell-derived exosome-like microvesicles in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2012: In press.

3. Zhang L, Xiao H, Karlan S, et al. Discovery and preclinical validation of salivary transcriptomic and proteomic biomarkers for the non-invasive detection of breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15573.

4. Zhang L, Farrell JJ, Zhou H, et al. Salivary transcriptomic biomarkers for detection of resectable pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(3):949-957.

5. Xiao H, Zhang L, Zhou H, et al. Proteomic analysis of human saliva from lung cancer patients using two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(2):M111.

6. Lee YH, Kim JH, Zhou H, et al. Salivary transcriptomic biomarkers for detection of ovarian cancer: for serous papillary adenocarcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl). Nov 18 2011. [Epub ahead of pr7. Floriano PN, Christodoulides N, Miller CS, et al. Use of saliva-based nano-biochip tests for acute myocardial infarction at the point of care: a feasibility study. Clin Chem. 2009;55(8):1530-1538.

8. Hu S, Wang J, Meijer J, et al. Salivary proteomic and genomic biomarkers for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3588-3600.

9. Glick M, Greenberg BL. The potential role of dentists in identifying patients’ risk of experiencing coronary heart disease events. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(11):1541-1546.

10. Greenberg BL, Glick M, Goodchild J, et al. Screening for cardiovascular risk factors in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(6):798-804.

11. Jontell M, Glick M. Oral health care professionals’ identification of cardiovascular disease risk among patients in private dental offices in Sweden. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(11):1385-1391.

About the Author

David T.W. Wong, DMD, DMSc

Associate Dean of Research

University of California Los Angeles, School of Dentistry

Dental Research Institute

Los Angeles, California

For information on Salivary Diagnostic products, visit: dentalaegis.com/go/id214