Achieving the Best Symmetrical Results from Two Zirconia Bridges

Luke Kahng, CDT

As everyone knows, most dental patients are very aware of the way their teeth look when they smile. Beautiful teeth have become much more attainable, and clinicians are very willing to educate people about their personal possibilities. With this in mind, patients will explore their options when they want to make changes. Sometimes, it may take a while for a patient to be ready to move forward, but when he or she decides, it is usually with a designated timeframe in mind.

In the case presented, a young lady in her early twenties was missing her laterals, teeth Nos. 7 and 10. She had been wearing a partial denture for years, but was tired of its presentation and her discomfort. Her other complaints were: a large black triangle between the two centrals, teeth Nos. 8 and 9; decalcification; discoloration; and size discrepancy. She also was unable to bite properly. As an adult with career decisions to be made and no longer under the constraints of extreme youth, she knew exactly what she needed to do to correct her teeth. In fact, implants had been considered but a visit to an oral surgeon determined that with her bone structure, implants were not an option.

Her dentist noted her tissue condition to be fair, and at his recommendation, she underwent laser surgery to recontour the ridges. She had no known allergies. At a later date, the dentist was able to accompany her to the laboratory for a custom shading appointment before preparation of her six anterior teeth. Her questions and concerns were addressed at that time, with the technician and the dentist both present to respond.

Case Presentation

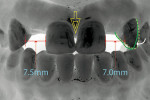

Preoperatively, the patient presented with discoloration and decalcification throughout (Figure 1). With her partial denture in place, the gaps between teeth Nos. 7 through 9 were slightly less noticeable, but this was still not a satisfactory situation for her. Her goal was to be partial-free. Without her partial denture in place (Figure 2), the gap between the centrals was more pronounced. Note the symmetrical problem the technician would encounter because of a difference in size where tooth No. 7 should have been (7.5 mm) and where tooth No. 10 should have been (7.0 mm). To achieve similarity of appearance in the two laterals, teeth Nos. 8 and 9 would have to be increased distally and teeth Nos. 6 and 11 increased mesially. The occlusal view of the partial in the mouth (Figure 3) underscored the patient’s need for a change. One aspect of note is that the canines were too protrusive outwardly and needed to be reduced in the technician’s wax-up design.

When fabricating the patient’s treatment plan wax-up, the technician gave definition and symmetry to her teeth by addressing the problems noted (Figure 4): the size differentiation between teeth Nos. 7 and 10, and the pronunciation of the canines, which needed cutting back slightly to create an even and harmonious appearance.

A hue check with shade tab No. CT-22 (Figure 5) brought out the patient’s orange-brown interproximal color. The application of cervical translucency would help to re-create the patient’s natural hue. Figure 6 demonstrates the dentist’s preparation design. Two three-unit zirconia porcelain bridges with ovate pontics would give the patient a metal-free and natural look.

After preparing the teeth, the dentist took impressions using Imprint™ light and heavy body (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN), and then fabricated the provisional teeth using Luxatemp®, shade A (Zenith/DMG Brand Division, Foremost Dental LLC, Englewood, NJ) (Figure 7).

Cementation of the temporaries led to a discussion about the structural differences between her natural teeth and the technician’s treatment plan wax-up design. Because of the increased width and incisal edge for teeth Nos. 7 and 10, the temporaries felt “different” to the patient. Through communication and discussion, the patient was kept informed about her case outcome and the size changes she could expect to see implemented.

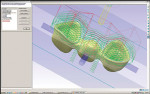

GC America Inc’s Advanced Milling Center (Costa Mesa, CA) supplied the laboratory with a computer-aided design/ computer-aided manufacture (CAD/CAM) design of the patient’s three-unit zirconia bridge (Figure 8). Without this precise blueprint, the team would not be able to predict symmetry. Also, the joint design had to be considered because the case involved two three-unit bridges, making their placement side-by-side in the patient’s mouth a paramount concern. The understructures were checked on the model for proper fit and contact (Figure 9) and again (Figure 10) with index putty from the wax-up as well as with frame modifier applied.

After the second buildup to the body and enamel, the copings were fired and index putty was applied to check the incisal room (Figure 11). Cervical translucency modifier from Initial™ Zr (GC America, Inc, Alsip, IL) (Figure 12) would help to create the proper hue. After firing, the technician again checked the incisal room against the wax-up’s index putty (Figure 13). To finish and properly contour the restorations, the technician applied glaze and gave himself a draft of his plan by applying two different marker colors to the teeth: orange to indicate where to create lobe, and black for crafting a secondary convex/concave shape to mimic natural teeth (Figure 14).

After this had been accomplished, one of the patient’s three-unit zirconia bridges was shown to advantage on a mirrored surface (Figure 15). The symmetry, hue, translucency, shape, and harmony of color would be reviewed after both bridges were tried in the patient’s mouth.

With the patient back in the dentist’s chair, the temporaries were removed using OptiClean™ (Kerr Corp, Orange, CA). The bridges then were placed permanently using RelyX™ Unicem (3M ESPE). The retracted posttreatment photograph (Figure 16) shows that symmetry was achieved. Through decreasing lateral size while increasing canine size and translucency for incisal edge coloring, the illusion of perfect symmetry was accom-plished. The natural-smile posttreatment photograph (Figure 17) shows a bright but subtle hint of her orange hue in the final color, which blended perfectly with her adjacent teeth. The final portrait photograph shows a beautiful young woman who has corrected function and no longer needs or worries about her partial denture and the appearance of her teeth (Figure 18).

Conclusion

In this case, longevity, as well as cosmetic issues, had to be considered. The patient required proper build-up to her case framework, margin, and design, especially in the interproximal areas of her teeth. The technician was able to achieve the desired result because of the consideration given to the two bridges' understructures and the porcelain layering technique used, with putty-perfect incisal edge positioning. All of the issues that needed correcting—symmetry, shape, size, lobe, contouring, occlusion, and increasing incisal height—were accomplished through constant communication and direction from the patient, dentist, technician, and the Advanced Milling Center.

The confidence a patient will gain from a new and corrected smile is reward enough for all of the hard work that goes into case preparation and planning. In this case, the author found it especially gratifying to help a young woman who had, for years, suffered from social embarrassment because of her teeth. Through communication, goal setting, and careful treatment planning, the patient was able to establish and achieve everything she had set out to do.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Dr. Leslie E. Russ, Naperville, Illinois, for performing the presented case.

About the Author

Luke Kahng, CDT

LSK121 Oral Prosthetics

Naperville, Illinois