Complete Denture Prosthodontics: Modern Approaches to Old Concerns

Joseph J. Massad, DDS; David R. Cagna, DMD, MS; William A. Lobel, DMD; Joseph P. Thornton, DDS

Contemporary complete denture therapy is undoubtedly steeped in a rich tradition of innovative techniques, clever processes, unique materials, and clinical precision. Though little has changed in principle over the years, modern complete denture wearers can expect to benefit from subtle, but significant, modifications of classic therapeutic philosophies. Most remarkable in today’s removable prosthodontic regimen are: (1) impression techniques employing anatomically optimized stock impression trays and state-of-the-art impression materials; (2) the revitalization of an old device designed to aid in establishing and registering a favorable mandibular treatment position; and (3) the modern application of an old occlusal concept incorporating recently redesigned posterior denture teeth and a tooth-arrangement philosophy that has been demonstrated to be favorable by sound, evidence-based clinical investigation.

Perhaps the most remarkable development that has emerged to assist in managing edentulism is implant dentistry. The application of dental implants to aid in the support, stability, and retention of removable dental prostheses has profoundly revolutionized the profession’s ability to satisfy this patient population’s treatment needs and desires. However, implant-assisted dental prosthetics will not be addressed here. Excellent and timely resources on this subject already exist in the professional literature.1-2 This discussion will be limited to modern and revitalized concepts impacting management of edentulism via conventional complete denture prosthodontics.

THE EDENTULOUS IMPRESSION

One of the most important aspects of high-quality complete denture therapy occurs early in the treatment sequence. Because complete denture fabrication is an indirect restorative procedure, an analogue of the edentulous ridges must be developed to be able to proceed with denture construction in the laboratory. The degree to which this analogue accurately represents oral contours and condition, both anatomically and functionally, determines in large part the quality of the therapeutic outcome. The method used to capture critical anatomic information for transport to the laboratory construction process involves making impressions of the denture-bearing tissues and peripheral structures and fabricating dental casts.

A wide variety of impression procedures has been described for conventional complete denture therapy.3-21 Procedures vary with respect to impression materials used, the design and construction of impression trays, intended extensions of peripheral borders, pressure delivered to denture-bearing tissues, and the incorporation of oral function during impression making. Conventional wisdom, as determined by experts in the field and taught in many US dental schools, involves impression-making procedures that include: (1) primary irreversible hydrocolloid impressions used to generate gypsum diagnostic casts; (2) construction of custom impression trays with varying design features; (3) intraoral adaptation of custom-tray border dimensions using border-molding techniques; and (4) definitive impressions made with a suitable impression material.22-25

Although conventional approaches to impression making in complete denture therapy have served the profession well over the years, the relatively recent appearance of new materials and devices provides an opportunity to rethink conventional wisdom. New materials and new anatomically designed stock impression tray systems permit the fabrication of accurate, pressure-controlled, definitive impressions without the need to develop custom impression trays.

Regardless of the edentulous impression technique selected, the procedure should produce casts that replicate critical anatomic features and operator-directed placement of the denture-bearing oral tissues. The following basic principles should be incorporated into all edentulous impression techniques:26

- Impressions should extend to include the entire denture foundation within the health and functional tolerance of the supporting and limiting tissues.

- Impression borders should be in harmony with the anatomic and functional limits of the denture foundation and adjacent tissues. Therefore, impression borders should be identified using functional movements.

- Adequate space for impression material within the impression tray must be available.

- A guiding mechanism, or stop, should be available to accommodate correct positioning of the impression tray relative to the edentulous ridge and associated tissues, particularly if multiple insertions of the impression tray are required.

- The impression tray and impression material should be made of dimensionally accurate and stable materials.

- Impression contours and dimensions should replicate intended contours and dimensions of the planned prosthesis.

A recently developed and refined method for edentulous impression making abides by these basic principles: it uses readily available, anatomically designed stock impression trays; it incorporates familiar vinyl polysiloxane (VPS) impression materials; and it is a relatively time-conservative procedure. Because this technique involves VPS impression materials varying in viscosity and flow characteristics, it may be broadly classified as a selective-pressure impression technique.23,27-33 As with all impression approaches and philosophies, reasonably healthy soft tissue conditions must be established before impression making.34-35 Subtle technique alterations are available for impressing poorly supported and clinically mobile soft tissues along the edentulous ridge crest.3,20,24-25,36-38 Great care must be taken in these situations to avoid ill-conceived placement, or random displacement, of mobile soft tissues during impression making that may adversely impact overall treatment success.

Although discussed in great detail elsewhere,39-42 this modern approach to impression making takes advantage of two recent developments: anatomically designed thermoplastic stock impression trays and a wide range of viscosity-specific VPS impression materials. Readers are encouraged to review the descriptive articles previously published detailing step-by-step impression-making procedures for conventional complete dentures, immediate complete dentures, implant overdentures, removable prosthesis relines, and external impressions.39-42 The current discussion will focus on highlights of the impression technique used during conventional complete denture construction.

Before initiating definitive edentulous impression procedures it is important that the impression tray accurately approximate the edentulous tissues. The trays used in the current technique are sufficiently rigid to maintain impression stability, appropriately sized to accommodate a variety of arch dimensions, thermoplastically formable for minor geometric alterations, and subtractively adjustable to permit extension modifications as needed. Additionally, tray handles are contoured to support correct lip posture and tray perforations aid in impression material retention.

For making the impression, a variety of VPS impression material viscosities are available. Thoughtful application of viscosity-specific materials at different times during impression procedures and in different areas of the tray permits a degree of tissue placement control. VPS, an addition-reaction silicone, offers a number of distinct advantages for making edentulous impression, including:

- Availability of different viscosities.

- Convenient delivery system (ie, automix cartridges).

- Predictable material adhesion between sequential layers of different material viscosities.

- Materials with various working times are available to satisfy operator preference. The material preferred by the authors (Aquasil Ultra Smart Wetting® Impression Materials Fast Set, DENTSPLY Caulk, Milford, DE) permits the operator approximately 30 seconds to dispense the material into the impression tray, 1 minute to insert the tray into the patient’s mouth and perform tissue manipulations, and 1 minute to final cure.

- The material is sufficiently elastic.

- The material has clinically acceptable tear strength.

- Newer materials in this class have been chemically modified to improve wettability or hydrophilicity.43-46

- The material is generally biocompatible.

- The material does not possess an offensive taste or odor.

In general, the steps used to make the edentulous impression include: (1) development of tray stops using high-viscosity VPS; (2) accomplishment of border-molding procedures using high- or medium-viscosity VPS; (3) trim tray overextensions using an acrylic resin carbide bur if the tray is seen to show through the border molding material; (4) reduce border molding and tray stops by 1 mm to 2 mm in all dimensions and according to selective pressure philosophy to provide impression space for the final wash material; and (5) introduce medium-, low-, and extra-low viscosity VPS materials into the tray and make the definitive impression. If excessively mobile soft tissues are present, care must be taken to provide additional tray relief and use an extra-low viscosity VPS in the affected areas of the impression. Once satisfied with the quality of the definitive impressions, bead, box, and cast the impression using a suitable vacuum-mixed dental stone.47

THE CENTRAL BEARING DEVICE

Once maxillary and mandibular master casts have been generated, it becomes necessary to accurately relate these casts to one another. Although clinicians have considered the virtues of various horizontal and vertical maxillo-mandibular relationships over the years, most agree on centric relation as a physiologically stable and repeatable mandibular treatment position.48 The practitioner’s ability to reliably produce and record this inter-arch relationship in patients is the function of a detailed understanding of the anatomy and physiology impacting temporomandibular joint function, effective handling of clinical materials and devices, patient cooperation, and operator skill and experience. Students and dentists alike are frequently frustrated by the challenge of making accurate and precise centric relation inter-occlusal records. Falling short of this important goal may significantly compromise therapeutic objectives and outcomes.

Historically, a number of techniques have been suggested for registering inter-arch relationships during complete denture construction, including direct inter-occlusal records, graphic recordings, and functional records. Direct inter-occlusal recording methods are frequently taught in US dental schools24 and are frequently used by clinicians in private practice. To achieve accurate and precise registrations using direct inter-occlusal methods, it is imperative that: (1) patients demonstrate cooperative and physiologically capable mandibular motion; (2) well-fitting, stable, and reasonably retentive record bases and occlusal rims are available; and (3) operators are experienced and skilled in the procedures being performed. The lack of any one of these factors can ultimately result in the recording of an inappropriate maxillo-mandibular relationship and treatment failure.

A graphic recording method dating to the turn of the 20th century involves the use of a central bearing device.49-50 Although not without reported drawbacks, incorporating a central bearing device during centric relation inter-occlusal registrations has long been considered a very precise recording method.51 This clinical approach has recently enjoyed a resurgence of interest spurred by the design and development of a rather unique and useful new device. This recent innovation makes use of the device readily applicable to the clinical procedure of acquiring and recording an accurate and precise centric relation mandibular position.

The new central bearing device comes complete with all of the elements necessary to assist in the registration of centric relation in various clinical situations, including dentulism, partial edentulism, edentulism, small-arch diameters, and large-arch diameters. All components are disposable, keeping pace with modern infection-control concerns. Setting the device up on record bases or para-occlusal bases is straightforward and time-conservative. The steps required to incorporate the new central bearing device into edentulous record bases are detailed in Figure 1; Figure 2; Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7; Figure 5; Figure 9; Figure 10; Figure 11.

LINGUALIZED OCCLUSION

The provision of successful removable dental prostheses for patients with substantially compromised denture-bearing foundations and reduced neuromuscular adaptive capacities may represent the most significant challenge facing today’s dental professionals. Much of the history of prosthodontics is devoted to addressing this challenge with commentary centering on topics such as anatomical changes in edentulism, impression philosophy, mandibular motion and articulator function, denture tooth forms, prosthetic occlusion, technical aspects of prosthesis construction, and maintenance of the therapeutic result. The professional desire to develop an optimal prosthodontic solution to edentulism has been significantly influenced by a concomitant search for the ideal artificial tooth form and arrangement. While anterior denture teeth are typically designed and developed with esthetics in mind, posterior denture teeth must take into account the mechanics and physiologic function of the edentulous stomatognathic system—our understanding of which is by no means complete.

In selecting a posterior denture tooth occlusion, a number of practical clinical and laboratory criteria must be considered. While valid arguments have been posed for the use of anatomic and non-anatomic tooth forms, no one form or arrangement has surfaced as universally applicable to all conditions seen in edentulous populations. However, one complete denture occlusal philosophy has relatively recently challenged this sentiment. To call this philosophy “novel” is misleading; a resurrection of old ideas wrapped in new and improved forms is more correct.

In 1972, the International Prosthodontic Workshop on Complete Denture Occlusion was held to appraise contemporary professional knowledge in this area.52 More recently, a review of clinical trials comparing the efficacy of different complete denture occlusal schemes was accomplished.53 Both of these reviews failed to identify a preponderance of scientific evidence supporting any particular posterior occlusal scheme for complete denture patients. In response to this apparent lack of clear evidence, Sutton and McCord carried out a randomized, controlled, cross-over clinical trial comparing anatomic, lingualized, and 0° posterior tooth occlusal forms for complete dentures.54

The results indicated that the lingualized occlusion was perceived to be superior to 0° occlusion in terms of reduced oral pain and incidence of sore areas, improved masticatory ability, and fewer meal interruptions. The anatomic occlusion proved better than 0° occlusion in terms of perceived masticatory function. Patients reported being “unable to eat” more frequently with 0° denture occlusion when compared to the other occlusal schemes. No significant differences were found to exist between lingualized and anatomic occlusions.

These results provide remarkable commentary on the complete denture occlusal schemes used in the patients studied. Most importantly, the experimental tactics applied to this important question were impeccable—a vast improvement over previous “scientific” efforts.

Application of lingualized occlusion is easy to comprehend from practical, functional, and analytical perspectives. As its name suggests, geometrically dominant and relatively sharp maxillary lingual cusps are set to articulate in relatively shallow mandibular fossae. This arrangement represents the characteristic “mortar and pestle” relationship often ascribed to lingualized occlusion. Incorporating an appropriate occlusal-compensating curvature, the mandibular posterior teeth are oriented to permit maxillary palatal cusp articulation into and out of the man-dibular fossae, while maintaining definitive sliding contact, during lateral and protrusive eccentric mandibular motion. This relationship permits occlusal balance through all eccentric mandibular positions. As a result, balance is not disrupted, and the facial cusps of maxillary posterior teeth can elevate away from occlusal contact in working and protrusive functions.

When refining occlusal contacts, either during laboratory or clinical remount procedures, the maxillary lingual cusps are never adjusted. These cusps must remain dominant and sharp to ensure optimal masticatory function. Occlusal refinement is primarily accomplished by adjusting the denture tooth structure emerging from the central fossae of the mandibular posterior teeth. A critical eye also must be directed to any contact developing along the maxillary posterior facial cusps. If detected, these contacts should be eliminated at the expense of the maxillary teeth. The practical benefits of this occlusal scheme may include: (1) improved esthetics as compared to flat occlusal schemes resulting from the presence of anatomically normal facial cusps on posterior teeth; (2) good masticatory efficiency resulting from dominant and sharp palatal cusps on maxillary posterior teeth; (3) the ability to achieve balanced occlusion; (4) controlled lateral force generation resulting from low cusp angles of mandibular posterior teeth; (5) easy occlusal scheme refinement during laboratory and clinical remount procedures; (6) relative ease in directly visualizing clinical occlusal inaccuracies requiring adjustment; and (7) a high rate of acceptance by patients.55-59

CONCLUSION

The professional development of new-and-improved impression procedures and methods for recording interocclusal jaw relationships, complete denture posterior tooth forms, and occlusal schemes are but a few of the innovations available to aid in the conventional treatment of edentulous patients. Though dental implant therapy has had a profound impact on the way dentistry approaches the management of edentulism, continued methodological improvements in conventional treatment regimens must keep pace with the ongoing needs of the ever-expanding edentulous population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Richard June, DDS; William J. Davis, Jr, DDS, MS; Samuel M. Strong, DDS; Mark E. Connelly, DDS; and William Pagan, DMD for their assistance in preparing this article.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Massad is responsible for the design of, and holds patents on, the impression trays and jaw recorder device discussed in this article.

References

1. Bryant SR, MacDonald-Jankowski D, Kim K. Does the type of implant prosthesis affect outcomes for the completely edentulous arch? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007; 22(suppl):117-139.2. Sadowsky SJ. Treatment considerations for maxillary implant overdentures: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97(6):340-348.

3. Ross RA. Zinc oxide impression pastes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1934;21:2029-2032.

4. Cotter SW. Zinc oxide paste—An impression material. Illinois Dent J. 1938;7: 392-398.

5. Trapozzano VR. Securing edentulous impressions with zinc oxide-eugenol impression paste. J Am Dent Assoc. 1939;26: 1527-1531.

6. Pearson SL. New elastic impression material: A preliminary report. Br Dent J. 1955;99:72-76.

7. Rosentiel E. Rubber base elastic impression materials (A preliminary note). Br Dent J. 1955;98(7):392-394.

8. Prothero JH. Prosthetic Dentistry. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Dental School; 1904:11-12.

9. Greene JW. Greene Brothers’ Clinical Course in Dental Prosthesis in Three Printed Lectures. 5th ed. Detroit, MI: Detroit Dental Manufacturing Company; 1916:17-49,89-115.

10. Clapp GW, Tench RW. Professional Denture Service. New York, NY: The Dentists’ Supply Company; 1918:14-96.

11. Wilson GH. A Manual of Dental Prosthetics. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1920;63-135.

12. Smith DE, Toolson LB, Bolender CL, et al. One-step border molding of complete denture impressions using a polyether impression material. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;41(3):347-351.

13. Christensen GJ. Impression materials for complete and partial prosthodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1984;28(2): 223-237.

14. Felton DA, Cooper LF, Scurria MS. Predictable impression procedures for complete dentures. Dent Clin North Am. 1996;40(1):39-51.

15. Tan HK, Hooper PM, Baergen CG. Variability in the shape of maxillary vestibular impressions recorded with modeling plastic and a polyether impression material. Int J Prosthodont. 1996;9(3):282-289.

16. Davis DM. Developing an analogue/substitute for the maxillary denture-bearing area. In: Zarb GA, Bolender CL, eds. Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients—Complete Dentures and Implant-Supported Prostheses. 12th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004:211-231.

17. Kois JC, Fan PP. Complete denture impressioning technique. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 1997;18(7):699-710.

18. Chaffee NR, Cooper LF, Felton DA. A technique for border molding edentulous impressions using vinyl polysiloxane material. J Prosthodont. 1999;8(2): 129-134.

19. Hayakawa I, Watanabe I. Impressions for complete dentures using new silicone impression materials. Quintessence Int. 2003;34(3):177-180.

20. Drago CJ. A retrospective comparison of two definitive impression techniques and their associated postinsertion adjustments in complete denture prosthodontics. J Prosthodont. 2003;12(3): 192-197.

21. Lynch CD, Allen PF. Management of the flabby ridge: Using contemporary materials to solve an old problem. Br Dent J. 2006;200(5): 258-261.

22. Arbree NS, Fleck S, Askinas SW. The results of a brief survey of complete denture prosthodontic techniques in predoctoral programs in North American dental schools. J Prosthodont. 1996;5(3):219-225.

23. Petropoulos VC, Rashedi B. Current concepts and techniques in complete denture final impression procedures. J Prosthodont. 2003;12(4): 280-287.

24. Petropoulos VC, Rashedi B. Complete denture education in U.S. dental schools. J Prosthodont. 2005;14(3):191-197.

25. Petrie CS, Walker MP, Williams K. A survey of U.S. prosthodontists and dental schools on the current materials and methods for final impressions for complete denture prosthodontics. J Prosthodont. 2005;14: 253-62.

26. Hickey JC, Zarb GA. Boucher’s Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients. 8th ed. St. Louis, MO: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1980:144-169.

27. Sharry JJ. Complete Denture Prosthodontics. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1974:191-210,295-309.

28. Edwards LF, Boucher CO. Anatomy of the mouth in relation to complete dentures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1942;29:331-345.

29. Boucher CO. Impressions for complete dentures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1943;30:14-25.

30. Boucher CO. A critical analysis of mid-century impression techniques for full dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1951;1:472-491.

31. Halperin AR, Graser GN, Rogoff GS, et al. Mastering the Art of Complete Dentures. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing Company, Inc; 1988:31-79.

32. Levin B. Impression for Complete Dentures. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing Company, Inc; 1984: 13-34,101-130,159-191,193-216.

33. Hickey JC, Zarb GA, Bolender CL. Boucher’s Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients. 9th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1985: 119-230.

34. Lytle RB. The management of abused oral tissues in complete denture construction. J Prosthet Dent. 1957;7:27-42.

35. Chase WW. Tissue conditioning utilizing dynamic adaptive stress. J Prosthet Dent. 1961;11:804-815.

36. Kelly E. Changes caused by a mandibular removable partial denture opposing a maxillary complete denture. J Prosthet Dent. 1972;27(2):140-150.

37. Xie Q, Nahri TO, Nevalainen JM, et al. Oral structures and prosthetic factors related to residual ridge resorption in elderly subjects. Acta Odontol Scand. 1997;55(5):306-313.

38. Carlsson GE. Clinical morbidity and sequelae of treatment with complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;79(1):17-23.

39. Massad JJ, Cagna DR. Vinyl polysiloxane impression material in complete denture prosthodontics. Part 1: Edentulous impressions. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2007;28(8):452-460.

40. Cagna DR, Massad JJ. Vinyl polysiloxane impression material in complete denture prosthodontics. Part 2: Immediate denture and reline impressions. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2007;28(9):519-527.

41. Massad JJ, Cagna DR. Vinyl polysiloxane impression material in complete denture prosthodontics. Part 3: Implant overdenture and external impressions. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2007;28(10): 554-561.

42. Massad JJ, Cagna DR. Immediate complete denture impressions—case report and modern clinical technique. Dent Today. 2008;27: 58-65.

43. Norling BK, Reisbick MH. The effect of nonionic surfactants on bubble entrapment in elastomeric impression material. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;42(3):324-347.

44. Pratten DH, Craig RG. Wettability of hydrophilic addition silicone impression material. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61(2):197-202.

45. Johnson GH. Impression materials. In: Craig RG, Powers JM, eds. Restorative Dental Materials. 11th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002:330-389.

46. Shen C. Impression materials. In:, Anusavice KJ, ed. Phillips’ Science of Dental Materials. 11th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2003: 205-254.

47. Rudd KD, Morrow RM, Feldmann EE. Final impression, boxing and pouring. In: Morrow RM, Rudd KD, Rhodes JE, eds. Dental Laboratory Procedures. Volume One: Complete Dentures. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1986:57-79.

48. Hickey JC. Centric relation. A must for complete dentures. Dent Clin North Am. 1964;8:587-600.

49. Gysi A. The problem of articulation. Dent Cosmos. 1910;52:1-19.

50. Sears VH. Centric jaw relation. Dent Dig. 1952;58: 302-306.

51. Kapur KK, Yurkstas AA. An evaluation of centric relation records obtained by various techniques. J Prosthet Dent. 1957;7:770-786.

52. Lang BR, Kelsey, CC. International prosthodontic workshop on complete denture occlusion. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan School of Dentistry; 1973.

53. Sutton AF, Glenny AM, McCord JF. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Denture chewing surface designs in edentulous people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(1):CD004941.

54. Sutton AF, McCord JF. A randomized clinical trial comparing anatomic, lingualized, and zero-degree posterior occlusal forms for complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97(5):292-298.

55. Parr GR and Loft GH. The occlusal spectrum and complete dentures. Compendium. 1982;3(4):241-249.

56. Clough HE, Knodle JM, Leeper SH, et al. A comparison of lingualized occlusion and monoplane occlusion in complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;50(2):176-179.

57. Lang BR, Razzoog ME. Lingualized integration: Tooth molds and an occlusal scheme for edentulous implant patients. Implant Dent. 1992;1(3):204-211.

58. Parr GR, Ivanhoe JR. Lingualized occlusion. An occlusion for all reasons. Dent Clin North Am. 1996;40(1):102-112.

59. Massad JJ, Connelly ME. A simplified approach to optimizing denture stability with lingualized occlusion. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2000;21(7):555-562.

|  | |

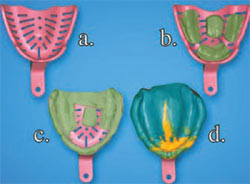

| Figure 1 (A) Size tray; (B) place tissue stops and trim excess; (C) place PVS to border bold and trim excess; (D) perform final wash. | Figure 2 (A) Size tray; (B) place tissue stops and trim excess; (C) place PVS to border bold and trim excess; (D) perform final wash. | |

|  | |

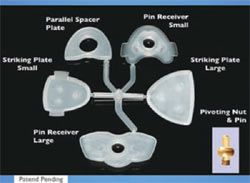

| Figure 3 Jaw relation recording device. | Figure 4 Fabricated record bases to mount jaw recorder. | |

|  | |

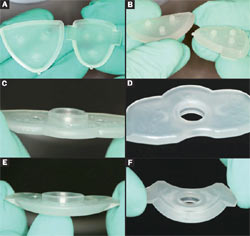

| Figure 5A through Figure 5F (A) Large- and small-size striker plates; working surface. (B) Largeand small-size striker plates; retentive mounting surface. (C) Large-size pin receiver; working surface. (D) Large-size pin receiver; retentive mounting surface. (E) Small-size pin receiver; working surface. (F) Small-size pin receiver; retentive mounting surface. | ||

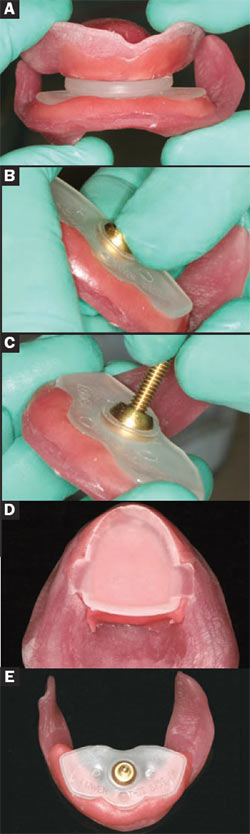

| Figure 6A through Figure 6D (A) Light-cure resin bonded to base plate; (B) place and position pin receiver; (C) cure into place; (D) mount parallel spacer plate. | ||

| ||

| Figure 8 Record occlusal vertical dimension and adjust pin height in the mouth to match occlusal vertical dimension. | ||

| ||

| Figure 9 The pin has been rotated to be perpendicular to the striking plate at the correct occlusal vertical dimension. | Figure 7A through Figure 7E (A) Parallel upper to lower device and cure; (B) after removal of parallel spacer plates, snap rounded nut into socket; (C) rotate pin into nut; (D) mounted striker plate; (E) mounted pin receiver with pin and nut. | |

| Figure 10A through Figure 10D (A) Place ink on striking plate and record centric record; (B) apex of arrow depicts centric record; (C) view of pin and recorded arrow; (D) adhere wax to lock plastic arrow guiding plate. | Figure 11A through Figure 11D (A) Guide patient to close into apex of arrow; (B) inject PVS bite registration material; (C) completed jaw recording. | |

| About the Authors | ||

Joseph J. Massad, DDS Joseph J. Massad, DDS Director of Removable Prosthodontics The Scottsdale Center for Dentistry Scottsdale, Arizona Associate Faculty Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Boston, Massachusetts Adjunct Associate Faculty Department of Prosthodontics University of Texas Health Science Center Dental School San Antonio, Texas | ||

| David R. Cagna, DMD, MS Professor and Director Department of Restorative Dentistry Advanced Prosthodontic Program University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Dentistry Memphis, Tennessee | ||

| William A. Lobel, DMD Clinical Assistant Professor Department of Prosthodontics and Operative Dentistry Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Boston, Massachusetts | ||

| Joseph P. Thornton, DDS Private Practice Snellville, Georgia | ||