Interdisciplinary Esthetic Management of Anterior Gingival Embrasures

Frank M. Spear, DDS, MSD

Achieving excellent esthetics in the anterior dentition requires that the interdental papilla and gingival embrasure form be managed so that an open embrasure doesn’t exist. In addition, the height of the adjacent papillae should be similar to provide a pleasing symmetry. This can be extremely challenging in the face of periodontal disease or malpositioned teeth.

It is always helpful to start any endeavor in dentistry with an image of what normal or ideal would be. In addition, it is helpful to know what may be acceptable while not ideal, and also to know what would be undesirable. This helps the practitioner understand what compromises in treatment are acceptable and which may not be.

With regards to the interdental embrasure and the papillae that occupy it, a study of well-aligned, unworn natural teeth found that, when comparing the length of the contact area and the height of the papilla, approximately a 50/50 relationship existed.1 That is, 50% of the overall tooth length was contact and the remaining 50% was papilla. This means that for a pair of 11-mm long central incisors, the contact would be 5 mm to 5.5 mm long and the papilla 5 mm to 5.5 mm tall. In addition, it has been shown that in these ideal circumstances the papilla is at the same level incisal-gingivally across all of the anterior teeth (Figure 1). This identifies the ideal but doesn’t describe what acceptable or unacceptable circumstances are. In general, two undesirable circumstances can occur. One may be that an isolated problem exists where a single papilla is more apically positioned than its neighbor. This is typically associated also with an open gingival embrasure or "black triangle." There are also times when an isolated papilla level problem is not associated with an open gingival embrasure but rather an excessively long contact. This can occur in the natural dentition because of tooth malposition, or in the restored dentition because of altering a restoration form to extend the length of the contact apically. In either case, lengthening of the contact in an apical direction makes the teeth look more square and less natural.

Whether this is an esthetic problem or not depends on where the long contact exists. If the problem area is between the central incisors but all the other papillae are normal, the long contact may not be as noticeable as it would be if it was between the central and lateral on only one side with all the other papilla being normal in height. In other words, the more asymmetric the long contact makes the smile left to right, the more visible it will be. The second possible problem that can lead to an unacceptable result is if all the papillae are positioned apically. This most commonly occurs with periodontal disease and results in multiple open gingival embrasures.

The challenge for the restorative dentist who has to restore these teeth is how to manage the outline form of the restorations: Create a natural-appearing tooth and leave open embrasures, or close the embrasures but create very square-looking restorations with long contacts? In general, as long as these contacts are equal in length and the papilla heights relatively level, the square tooth form is esthetically preferable to the open embrasures (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Having identified what the acceptable outcomes of treatment may be, it is time to examine the specific options available to achieve these goals. It is very helpful to understand that any time an open embrasure exists it is because of a papilla not extending coronally enough to fill the embrasure, or a contact not extending apically enough to reach the papilla. To start diagnosing which of these areas is a problem, we will begin by discussing the papilla as an entity unto itself.

The height of the papilla is determined by three things: the level of the interproximal bone, the patient’s biologic width, and the size and shape of the gingival embrasure of the teeth (Figure 4). As the interproximal bone levels move coronally, such as in tooth eruption, the papilla moves coronally. As the bone level moves apically, such as in periodontal disease, the papilla has the potential to move apically. The distance the papilla stands above the bone is influenced by the remaining two factors, the patients’ biologic width and volume of the gingival embrasure. Although the average biologic width (the combined height of the connective tissue attachment and the epithelial attachment) is 2 mm, Vacek found large variations from .75 mm to 4.3 mm in cadavers.2,3 The possible variations may result in some papillae extending significantly more coronal above bone than average. In addition to the variations in biologic width, variations in gingival embrasure form can significantly alter the height of the papilla.

If you think of the floor of a room as the bone, and the legs on a desk as the biologic width, imagine placing a water balloon on the desk between your hands. This effectively is the tissue that sits coronal to the patient’s biologic attachment. If you now move your hands farther apart, the water balloon will sag and become shorter in height relative to the desktop. If, on the other hand, you squeeze your hands together, the balloon will move higher above the desktop. This is the same impact that altering embrasure form has on papilla height. The more open the embrasure, the flatter and more apical the papilla will be. The more closed the embrasure, the more pointed and coronal the papilla will be. It becomes obvious then why periodontal disease can result in such significant black spaces. Not only is the bone moving apically, but if the papilla recedes it now moves into a much more open embrasure, causing it to flatten out and move even more apically.

It is helpful, then, to know in general where the height of the papilla is relative to the bone. Van der Veldon evaluated this by removing papilla completely and then following their regeneration over a 3-year period.4 During this time he found regeneration on average of 4 mm to 4.5 mm above the bone with a sulcus depth of 2 mm to 2.5 mm. It would appear, then, that the height of the papilla will always be at least 4 mm to 4.5 mm above the bone as long as the teeth are present.

Tarnow took a different approach, evaluating the heights of the contact above the interproximal bone and asking the question of whether the papilla filled the space or not. When the contact was 5 mm from the bone, the papilla always filled the space, which is logical in light of Van der Veldon’s findings. When the contact was 6 mm from the bone, the papilla filled the embrasure 56% of the time. And when the embrasure was 7 mm tall, only 27% of the time did the papilla fill it (Figure 5). In general, then, a contact above the bone of 4.5 mm to 5 mm should always be filled by the papillae.

It is important to note, however, that in some patients a papilla of 6 mm or even 7 mm above the bone may be normal and stable if they have a biologic width significantly taller than 2 mm. For this reason, the author often uses sulcus depth rather than the distance above the bone as a way of assessing the likely behavior of a papilla during treatment. If a papilla is 6 mm or 7 mm above the bone but has a sulcus depth of 2 mm or 3 mm, it is probably fairly stable. If, on the other hand, it has a sulcus depth of 5 mm it may recede during treatment. Recession is also linked to the biotype of the patient, ie, thick vs thin (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

With an understanding of the biology of the interproximal papilla, it is now possible to discuss diagnosis and treating specific clinical situations. To begin with a common problem, imagine a patient who presents unhappy with an open gingival embrasure between an isolated pair of anterior teeth. As already discussed, this could occur because of a papilla that is apically positioned, or a contact that doesn’t extend apically enough.

To diagnose which situation it is, begin by evaluating the height of the papillae in the problem area and comparing it to the height of the adjacent papilla that do not have an open embrasure. Two findings are possible. One is that the papilla in the problem area is even with the adjacent papillae, in which case the problem is that the contact doesn’t extend apically enough.

The second reason is that the papilla in the problem area is apical to the adjacent papillae. Two possible reasons exist for this finding. The first reason is that there is bone loss in the problem area that results in the apical migration of the papilla. The second reason is that if the bone is normal, and the papilla is apically positioned—and not recently traumatized—the embrasure is too wide and results in a flattening of the papilla. Often this can be ascertained by probing the sulcus. Because we know that even after surgical removal the papilla will regenerate a sulcus depth of 2 mm to 3 mm, any probing less than 2 mm almost guarantee that the papilla will move coronally by narrowing the gingival embrasure to at least a sulcus of 2 mm to 3 mm (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

If the papilla is found to be apical to the adjacent papillae that do not have an open embrasure, then two treatment options exist. One, if the bone is the problem, then treatment will need to bring the bone coronal. Unfortunately, doing this by grafting bone between adjacent teeth in a coronal direction is rarely, if ever, successful.7 What is successful, however, is to orthodontically erupt the bone by erupting the teeth adjacent to the problem area.8,9 As long as the area is healthy, the interproximal bone will move coronally as will the papilla. As the eruption progresses, however, it will be necessary to shorten the incisal edges of the teeth being erupted, resulting in a decrease in overall crown length. This then must be compensated for by crown lengthening the facial of the teeth being erupted by removing facial bone and tissue and not touching the interproximal bone and tissue. This technique can be used on isolated areas or across the entire anterior if there has been horizontal bone loss across all of the anterior teeth.

The second possible finding when the isolated papilla was apical to the desired level was that the bone wasn’t the problem, but that the embrasure was too large. This can result in an open embrasure even when papilla levels are ideal.

Two typical problems can create embrasures that are too large or contacts that do not extend apically enough—divergent roots or tapered crown forms. If the papilla levels are correct and the embrasure is open, it will be necessary to extend the contact in an apical direction, which at the same time decreases the volume of the embrasure and potentially increases the height of the papilla as well. To determine whether this should be accomplished by correcting the root angulation using orthodontics or altering crown contour, start by taking a radiograph of the teeth to evaluate the roots for divergence. If the roots are divergent, orthodontics often is the ideal solution to create ideal papilla levels.

Paradoxically, this problem can be created by orthodontics, specifically in an adult with overlapped incisors.10 For the incisors to be overlapped, the roots have to be divergent. However, in an adult, the incisal edges may be worn even. When an orthodontist now places brackets level to these worn incisal edges and begins to align them, the roots remain divergent and the contact moves incisally, opening the gingival embrasure and creating a large black space. This may often be unrecognized and instead be diagnosed as a periodontal problem. However, by simply replacing the brackets perpendicular to the mesial surface and replacing the arch wire as the roots become more parallel, the contact moves apically, the embrasure decreases in size, and the papilla moves coronally to its ideal level. It is almost always necessary, however, to now restore the incisal edges because of the wear that existed at the start of treatment. In addition, the patient needs to be made aware that during the orthodontic therapy to correct the gingival embrasures, the incisal edges will begin to look worse until they are restored (Figure 10; Figure 11; Figure 12).

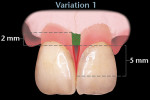

Another possibility is to evaluate the root angulation and find it to be parallel, yet the contact does not extend apically far enough to contact a normal papilla. This is most commonly the result of a crown form that is excessively tapered. Two options exist to resolve this problem. One is to reshape the teeth by discing their interproximals to create small diastemas, followed by orthodontically closing the spaces and extending the contact apically. The downside of this approach is two-fold. The teeth are narrowed, potentially creating a less pleasing width-to-length ratio, and the patient requires orthodontics. Far more commonly, the solution to correct overly tapered crown form is restoration, either directly with composite or indirectly with veneers or crowns. The greatest challenge in using restorations to alter interproximal embrasure form is for the clinician to realize that the restorations must be carried subgingivally to gradualize the contour change. Attempting to leave the margins at gingival levels will leave ledges of restorative material and will not impact the papillary form (Figure 13; Figure 14; Figure 15).

When using indirect restorations to close an open gingival embrasure, not only do the margins need to be carried subgingivally 1 mm to 1.5 mm, but the technician must fabricate the restorations on a model that has the soft tissue profile present to be able to correctly produce the desired interproximal embrasure form. It is often necessary for the technician to reshape the papilla on the soft tissue model before fabricating the restorations.

The restorations are then produced against the idealized papilla form of the soft tissue model. When the restorations are then placed on the teeth, the papilla conforms to the idealized shape that was originally created on the soft tissue model (Figure 16; Figure 17; Figure 18; Figure 19).

A common thought when looking at patients with open embrasures would be to have the periodontist graft the papilla. As discussed earlier, grafting interproximal bone is not predictable, but what about grafting soft tissue?

The challenge of grafting soft tissue is one of attempting to create what we identified as an unstable papilla. That is, the bone and the biologic width will not be altered by the graft, but rather the graft simply adds more unattached tissue, creating a deeper sulcus that is then likely to recede.

The areas the periodontist can impact—gingival embrasure form and, therefore, tooth form—is by altering the gingival scallop. That is, leaving the papilla alone during surgery and removing only facial bone and gingiva. This has the impact of making the papillae appear taller and allowing a more pleasing crown form to be created restoratively. The downside of this approach is that it also increases overall crown length. It is particularly effective for patients with a flat periodontium and short teeth (Figure 20; Figure 21; Figure 22; Figure 23). If the teeth are of normal length, scalloping the gingiva can be used to enhance the appearance of the papilla but it may be necessary to first erupt the teeth, shortening the incisal edges during the eruption and thereby reducing the overall tooth length and contact length before the facial crown-lengthening surgery.

The last area to be discussed is the situation where the contact area is too short but there is no open embrasure. This almost always occurs in cases of severe tooth wear. The incisal edges of the teeth wear away, reducing the contact length, but the papilla and gingival embrasure remain normal. In these patients the first diagnostic step is to determine if the teeth and gingiva have erupted as they wore.11 This is typically confirmed by evaluating the incisal edge of the anteriors relative to the face. If the incisal edges of the worn anteriors are correctly positioned and level with the occlusal plane, it is highly likely that the teeth erupted as they wore away, in which case the papilla and free gingival margins will be coronally positioned compared to ideal. This is generally easy to confirm by comparing the gingival margins on the centrals with the level of the canines. If the centrals are significantly coronal to the canines, then the teeth erupted as they wore away. This results in a normal-looking papilla and gingival scallop but a short contact.

Two solutions exist for this. One is to orthodontically intrude the incisors. This will move the papilla and free gingival margins back to their original position. The teeth can then be restored, adding back the worn incisal edge and correcting the contact length. There are two challenges with this approach. First, it is slow and may require a year or more of orthodontics. Second, if the teeth are severely worn, it is critical to determine if adequate tooth structure exists to restore them before intrusion; otherwise, it is possible to intrude the teeth to an ideal level and then consider crown lengthening to expose tooth structure.

The other area to keep in mind during intrusion is that the contact length is increasing but the papilla height is not. This means that in cases of a relatively flat periodontium, it may be beneficial to use some intrusion and some facial surgery to create a more ideal relationship between papilla height and contact length, as opposed to only intrusion and excessively long contacts.

The alternative to using intrusion is to use periodontal crown lengthening in cases of wear and secondary eruption. Only now it will be necessary to apically position both the papilla and facial tissue. The advantages of crown lengthening are that it exposes tooth structure for the restorative dentist and also can idealize the papilla height and gingival margin position to create an ideal gingival scallop. The disadvantage is that the restorative dentist is now working on a narrower area of the tooth so that tooth contours and gingival embrasure form may need to be altered from normal to avoid "black triangles." The author has, however, never avoided crown lengthening purely because of the narrowness of the roots. Root length, on the other hand, has to be good to perform this type of crown lengthening (Figure 24; Figure 25; Figure 26; Figure 27; Figure 28).

The alternative finding in the patient with wear and a short contact may be that the teeth have not erupted as they have worn. In that case, the treatment plan needs to be focused on gaining space so that the incisal edges can be restored to their correct position, re-creating a normal length contact and proportion to the tooth.

In concluding this discussion on the interdisciplinary management of gingival embrasure form, it is critical that whatever problem you, as the clinician, per-ceive with a cervical embrasure be properly diagnosed. Is it a bone level problem, an embrasure volume problem, or simply inadequate contact length? It is then possible to consider from all the treatment options outlined to solve each of these different problems. It is safe to say, however, that esthetically managing gingival embrasures ideally requires an interdisciplinary team approach to achieve an optimal esthetic outcome.

References

1. Kurth JR, Kokich VG. Open gingival embrasures after orthodontic treatment in adults: prevalence and etiology. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:116-123.

2. Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B. Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans. J Periodontol. 1961;32: 261-267.

3. Vacek JS, Gher ME, Assad DA, et al. The dimensions of the human dentogingival junction. Int J Periodont Rest Dent. 1994;14(2):154-165.

4. Van der Velden U. Regeneration of the interdental soft tissues following denudation procedures. J Clin Periodontal. 1982;9(6):455-459.

5. Tarnow DP, Magner AW, Fletcher P. The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol. 1992;63(12):995-996.

6. Sanavi F, Weisgold AS, Rose LF. Biologic width and its relation to periodontal biotypes. J Esthetic Dent. 1998;10(3):157-163.

7. Blatz MB, Hurzeler MB, Strub JR. Reconstruction of the lost interproximal papilla—presentation of surgical and non-surgical approaches. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19(4):395-406.

8. Kokich VG, Spear FM, Kokich Jr VO. Maximizing anterior esthetics: An interdisciplinary approach. In: Frontiers of Dental and Facial Esthetics. McNamara Jr JA, Kelly KA, eds. 2001:1-18.

9. Kokich VG. Esthetics: The orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthod. 1996;2(1):21-30.

10. Ikeda T, Yamaguchi M, Meguro D, et al. Prediction and causes of open gingival embrasure spaces between mandibular central incisors following orthodontic treatment. Aust Orthod J. 2004;20(2):87-92.

11. Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:160-169.

About the Author

Frank M. Spear, DDS, MSD

Founder and Director, Seattle Institute for Advanced Dental Education

Seattle, Washington

Affiliate Assistant Professor, University of Washington School of Dentistry

Seattle, Washington

Private Practice

Seattle, Washington