You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on AEGIS Dental Network is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Clinical Guide to Treating Endodontic Emergencies

Avoiding common mistakes to provide optimal outcomes

James Bahcall, DMD, MS | Bradford Johnson, DDS, MPHE

An endodontic emergency “is defined as pain and/or swelling caused by various stages of inflammation or infection of the pulpal and/or periapical tissues.”1 An American Dental Association 2010 survey stated that general dental practitioners averaged 230.7 walk-in/emergency patients per year.2 Approximately 85% of all dental emergencies arise from pulpal or periapical disease.3

The patient with an endodontic emergency requires a clinician to be skilled in diagnosis, endodontic treatment, and clinical pharmacology.4 With the correct implementation of these skills, a dentist can be efficient and effective in treating a patient with an endodontic emergency. This article will discuss the clinical management of an endodontic (non-trauma, adult patient) emergency from diagnosis through treatment.

Diagnosis

After reviewing the patient’s medical and dental history, the determination of the pain etiology must be made prior to performing any emergency treatment. The first step in determining etiology is understanding the patient’s perception of the issue (subjective), followed by clinical tests (objective) to reproduce the patient’s subjective pain symptoms.

There are five objective clinical tests that need to be performed in a patient’s endodontic diagnostic evaluation:

1. cold, electric pulp tester (EPT) and/or heat tests for pulp vitality

2. percussion testing to determine the status of the periodontal ligament (PDL) 3. palpation testing to evaluate the gingival tissue and cortical and trabecular bone for infection or inflammation

4. periodontal examination that includes probing and tooth mobility evaluation

5. radiographic examination of current periapical and bitewing films, along with a CBCT (cone-beam computed tomography) when indicated.

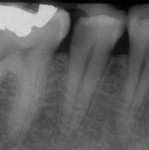

These objective tests enable a dentist to make a proper pulpal and periradicular diagnosis. Using only a dental radiograph to determine the etiology of tooth pain can lead to treatment of the wrong tooth (Figure 1).

Pulpal and Periradicular Diagnoses

The pulpal nerve fibers A-delta (respond to cold and EPT) and C-fibers (respond to hot and patient’s report of spontaneous tooth pain) are nociceptors, which are sensory receptors that respond to stimuli by sending nerve signals to the brain. This stimulus can cause the perception of pain in an individual.5 By testing the pulpal nerve fibers, a dentist can determine the pulpal status.

Current pulpal diagnosis terminologies include:

• Reversible pulpitis: Pain from an inflamed pulp that can be treated without the actual removal of the pulp tissue. This is not a disease, but rather a symptom. The classic clinical symptom is a sharp, quick pain that subsides as soon as the stimulus (cold) is removed.

• Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: Pain resulting from an inflamed pulp for which the only treatment is removal. Classic clinical symptoms include lingering of cold/hot stimulus for more than 5 seconds and/or patient reporting spontaneous tooth pain.

• Pulpal necrosis: The pulp does not respond to cold tests, EPT, or heat test. Pulpal necrosis can result from an untreated irreversible pulpitis or immediately after a traumatic injury that disrupts the vascular system of the pulp.

A periradicular diagnosis is just as important as a pulpal diagnosis. A study by McCarthy and colleagues6 demonstrated that patients presenting with periradicular pain can localize the painful tooth (89%) in comparison to patients that present with tooth pain without periradicular pain (30%). Current periradicular diagnosis terminologies are described in Table 1.

Odontogenic vs Non- Odontogenic Pain

When performing objective clinical endodontic tests to diagnose an emergency endodontic patient, there can be many non-odontogenic pain symptoms that mimic endodontic symptoms.7 If a patient describes his or her pain as tingling, electric-like, burning, or hurting on both sides of the face, the etiology may be non-odontogenic in origin.

Whenever the objective endodontic diagnostic tests either do not correlate with the subjective patient symptoms or are within normal limits, a clinician must re-evaluate the etiology of pain and proper diagnosis before providing any dental treatment.

When confirming endodontic pain, primary pain is when the reported and actual site and source of the pain are the same. For example, this occurs if patients report that their tooth pain is brought on when they eat or drink anything cold and you test the specific tooth to cold and they have a painful lingering response (pulpal diagnosis: symptomatic irreversible pulpitis).

Heterotopic pain or secondary pain is perceived to originate from a site that is different from the actual source of the pain.7 From an endodontic diagnostic perspective, the dentist must consider that the source of the pain is different from the site of the pain when the tooth perceived as the pain source tests within normal limits to the objective tests. In this case, endodontic treatment on the tooth will result in no change in the patient’s pain.

Selective anesthesia can be useful to either isolate odontogenic pain or help differentiate between odontogenic and non-odontogenic pain. As a clinical guide, if the tooth pain subsides after anesthesia is placed, the etiology is most likely odontogenic pain. If the patient’s pain does not subside after injection of local anesthesia, the clinician should consider a non-odontogenic etiology.8 Although selective anesthesia can be a useful clinical aid in diagnosis, it should be performed as a last objective test after all the tooth and periradicular testing has been completed.

Pretreatment Local Anesthesia

It is paramount for a clinician to obtain profound anesthesia when treating an endodontic emergency patient. A common mistake that clinicians make when attempting to get a patient “numb” is not objectively testing if pulpal anesthesia has been achieved prior to initiating endodontic treatment. Often, this determination is made by the “subjective” viewpoint of the patient. Studies have demonstrated that inferior alveolar nerve blocks (IANBs) administered to patients with mandibular teeth diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis had an average incidence of pulpal anesthesia of 55%, even in the presence of profound lip numbness.9,10

Prior to giving local anesthesia for endodontic treatment, objectively test the treatment tooth with cold and/or EPT (Figure 2). With a preoperative baseline of the pulp vitality, the level of anesthesia can be accessed by re-testing the treatment tooth with cold or EPT once anesthesia is “on board.” If the post-anesthesia tests are negative to cold or reveal an 80 EPT reading, there is a strong chance that the patient has achieved pulpal anesthesia.

Regional and Supplemental Local Anesthesia

Another common clinical mistake when trying to achieve profound pulpal anesthesia is only giving an infiltration around the treatment tooth. This may be effective for treating a small cavity, but not for endodontic treatment. The dentist should first administer a regional block for local anesthesia. A regional block for the mandible is the IANB and for the maxilla, it is the superior alveolar nerve block (SANB). If profound anesthesia cannot be achieved with a regional block alone, a supplemental block needs to be administered. Supplemental local anesthesia injection examples include long buccal nerve blocks (mandibular molars), PDL, intraosseous, and intrapulpal. When administered prior to a regional block, supplemental anesthesia will neither be long acting nor effective enough to provide pulpal anesthesia. Also, re-injection of local anesthesia in the same regional or supplemental site has shown increased success rates in achieving pulpal anesthesia.9

Endodontic Treatment

After proper diagnosis and profound local anesthesia, one can proceed with clinical endodontic treatment. Often in a busy practice, a dentist will simply prescribe pain medication and re-appoint the unscheduled emergency patient. However, performing endodontic treatment can significantly reduce odontogenic pain due to acute pulpal inflammation.4 The endodontic treatment can be a pulpotomy (removal of the coronal pulpal tissue only) or pulpectomy (the complete removal of the pulp tissue). Studies have demonstrated that a pulpotomy and pulpectomy will reduce preoperative tooth pain.11,12 A pulpectomy should be performed in necrotic pulp cases or in vital pulp cases where the clinician has enough time in their schedule.

When performing a pulpectomy, chemomechanical preparation of the entire root canal system should be done. This type of chemomechanical canal preparation involves using endodontic files, sodium hypochlorite, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) placement on each file (Figure 3). Also, if the dentist is not doing a single-visit treatment, calcium hydroxide should be placed in the canal(s) prior to temporizing the tooth in cases of irreversible pulpitis.13 If the canal(s) is/are necrotic, it is recommended to also irrigate the canal(s) with chlorhexidine prior to placing a calcium hydroxide in the canal and temporizing the tooth.14

Hand files should be used initially to access the root canal, create a glide path, and determine working length. Hand files should then enlarge the canal at working length to at least a 20/.02 to 30/.02 size file. This will depend on the tooth that is being treated. After this step, rotary file instrumentation should be initiated. It has been documented in the literature that rotary nickel-titanium files can prepare a canal faster than hand files.15

Although there are many different file techniques for conventional endodontic treatment, a consistent and efficient method of treatment is using a “modified crown down” technique.16 This technique involves first opening the coronal two thirds of the canal with rotary files. Next, take rotary files to working length and work them up from smaller to larger size files. If the operator is using lateral compaction for obturation, a 0.04 taper file is best and if obturating with a thermoplastic obturation technique, a 0.06 taper file is recommended. The last file size with the ability to be taken to working length in a canal is considered the master apical file.

When performing endodontic emergency and non-emergency treatment, a clinician must use a rubber dam for tooth isolation. Also, the occlusion should be adjusted prior to endodontic access on posterior teeth. This will help provide consistent file reference points and help reduce postoperative PDL inflammation.17

Post-Treatment Medication

The most consistent factor that can predict postoperative endodontic pain is the presence of preoperative hyperalgesia (spontaneous pain, reduced pain threshold, and/or increased perception to noxious stimuli).18 Another common clinical mistake is prescribing drugs post-treatment and not critically assessing if they are pharmacologically treating inflammation and/or infection. Often, a dentist will prescribe antibiotics for tooth pain that has an inflammatory etiology. Fouad19 reported that antibiotics do not have any analgesic effect in odontogenic pain. A clinical guide for determining if inflammation and/or infection is the pre-treatment endodontic and periradicular diagnosis. If the treatment diagnosis is irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis, this is strictly inflammation and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the medication of choice.

Significant reduction in odontogenic pain can be seen from taking 400 to 800 mg of ibuprofen.20 In cases when ibuprofen alone is not effective in reducing postoperative pain for the emergency endodontic patient, administering a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can produce significantly effective pain management from odontogenic type inflammation.21 Acetaminophen, alone or in combination with an opioid (eg, codeine or hydrocodone), is a good alternative analgesic in patients who cannot take NSAIDs.4

There will be cases in which NSAIDs do not help a patient’s odontogenic postoperative pain. Although opiate medications are commonly prescribed in these case scenarios, a dentist should also consider prescribing dexamethasone (eg, Decadron®, Merck & Co, Inc., www.merck.com),22 a synthetic adrenocortical steroid. If there is an odontogenic infection, the patient should take an antibiotic as well, because steroids can block or mask the body’s response to infection. When Decadron is prescribed, patients should discontinue any NSAIDs they are currently taking for pain.

In the emergency patient case where the pulpal diagnosis is necrotic pulp and periradicular diagnosis is either acute apical abscess or symptomatic apical periodontitis, prescribing an antibiotic is recommended. An antibiotic should also be prescribed to patients with systemic signs of infection (ie, fever, swelling, malaise, or compromised airway), cellulitis, and medically compromised patients.

Penicillin V potassium (Pen VK) is the antibiotic of choice for endodontic-type infections. Studies demonstrate that the Pen VK spectrum of microbial activity includes bacteria that have been isolated in endodontic infections.23 Clindamycin is the second antibiotic of choice. Clindamycin is beta-lactamase resistant (unlike Pen VK) and has a good spectrum against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.24

It is important to use a loading dose when prescribing antibiotics. Antibiotics with long half-lives can require several days of therapy to achieve effectiveness. The most critical time for antibiotic effectiveness is the first 24 hours because this is typically when inoculum of infection is high and likely to harbor resistant subpopulations of bacteria.25,26

An antibiotic regimen in endodontic treatment should be 7 to 10 days. Although a patient should respond to antibiotic therapy within 24 to 48 hours, the patient needs to stay on the antibiotic until finished to prevent a rebound effect of the active infection. Also, the dentist should be in close contact with an emergency patient on antibiotics in the event that clinical symptoms worsen or there is a drug allergy.27 Lastly, if the emergency endodontic patient presents with intraoral fluctuant swelling, the clinician should perform an incision and drain procedure.28

Conclusion

Properly treating endodontic emergency patients requires the dentist to have a good understanding of diagnosis, local anesthesia, conventional endodontic treatment, and clinical pharmacology. Through the understanding of these clinical skills, a dentist will find treating the emergency endodontic patient to be as routine as performing endodontics on a non-emergency patient. The successful treatment of the endodontic emergency patient will also be gratifying to both doctor and patient.

Disclosure

James Bahcall, DMD, MS, and Bradford Johnson, DDS, MPHE, have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

References

1. Wolcott J, Rossman LE, Hasselgren G. Management of endodontic emergencies. In: Hargreaves KM, Cohen S, eds. Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2011:40-48.

2. American Dental Association 2010 Survey of Dental Practice. April 2012. www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/10_sdpc.ashx. Accessed October 16, 2015.

3. Mitchell DF, Tarplee RE. Painful pulpitis: a clinical and microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1960;13:1360-1370.

4. Hargreaves KM, Keiser K. New advances in the management of endodontic pain emergencies. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(6):469-473.

5. Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain. 2008;137(3):473-477.

6. McCarthy PJ, McClanahan S, Hodges J, Bowles WR. Frequency of localization of the painful tooth by patients presenting for an endodontic emergency. J Endod. 2010;36(5):801-805.

7. Okeson JP, ed. Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing. 1996;8:69.

8. Kulild J. Diagnostic testing. In: Ingle J, Bakland, L, Baumgartner J, eds. Ingle’s Endodontics 6. 6th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2008: 542.

9. Cohen HP, Cha BY, Spangberg LS. Endodontic anesthesia in mandibular molars: a clinical study. J Endod 1993;19:370-373.

10. Nusstein J, Reader A, Nist R, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of the supplemental intraosseous injection of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 1998;24(7):487-491.

11. Hasselgren G, Reit C. Emergency pulpotomy pain relieving effect with and without the use of sedative dressings. J Endod. 1989;15(6):254-256.

12. Hargreaves KM. Management of pain in endodontic patients. Tex Dent J. 1997;114(10):27-31.

13. Bahcall J. Everything I know about endodontics, I learned after dental school, Part 1. Dent Today. 2003;22 (5):84-89.

14. Kuruvilla JR, Kamath MP. Antimicrobial activity of 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate separately and combined, as endodontic irrigants. J Endod. 1998;24(7):472-476.

15. Short JA, Morgan LA, Baumgartner JC. A comparison of canal centering ability of four instrumentation techniques. J Endod. 1997;23(8):503-507.

16. Pryles R, Short R, Bahcall J, Nasseh A. Advances in endodontics. Inside Dentistry. 2015;11(10):44-51.

17. Rosenberg PA, Babick PJ, Schertzer L, Leung A. The effect of occlusal reduction on pain after endodontic instrumentation. J Endod. 1998;24(7):492-496.

18. Mattscheck DJ, Law AS, Noblett WC. Retreatment verse initial root canal treatment: factors affecting posttreatment pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(3):321-324.

19. Fouad AF, Rivera EM, Walton RE. Penicillin as a supplement in resolving the localized acute apical abscess. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81(5):590-595.

20. Torabinejad M. Cymerman JJ, Frankson M, et al. Effectiveness of various medications on postoperative pain following complete instrumentation. J Endod. 1994;20(7):345-354.

21. Cooper SA. The relative efficacy of ibuprofen in dental pain. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1986;7(8):578, 580-581.

22. Krasner P, Jackson E. Management of posttreatment endodontic pain with oral dexamethasone: a double-blind study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62(2):187-190.

23. Vigil GV, Wayman BE, Dazey SE, et al. Identification and antibiotic sensitivity of bacteria isolated from periapical lesions. J Endod. 1997;23(2):110-114.

24. Gilmore WC, Jacobus NV, Gorbach SL, et al. A prospective double-blind evaluation of penicillin versus clindamycin in the treatment of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(12):1065-1070.

25. Drusano GL. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of “bug and drug.” Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(4):289-300.

26. Martinez MN, Papich MG, Drusano GL. Dosing regimen matters: the importance of early intervention and rapid attainment of the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics target. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(6):2795-2805.

27. Bahcall J. Everything I know about endodontics, I learned after dental school, Part 2. Dent Today. 2003;22(8):62-68.

28. Newman M, Kornman K. Antibiotics/Antimicrobial Use in Dental Practice. 1st ed. Chicago, IL: Quintessence; 1984:152.

About the Authors

James Bahcall, DMD, MS

University of Illinois

College of Dentistry

Chicago, Illinois

Bradford Johnson, DDS, MPHE

University of Illinois

College of Dentistry

Chicago, Illinois