You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Mechanism of Action

Pulsation and pressure are the critical mechanisms in the action of a dental water jet. The combination provides for phases of compression and decompression of the gingival tissue to remove supragingival plaque biofilm and expel subgingival bacteria and other debris as well as stimulating gingival tissue.1 In comparison, studies have shown that a pulsating device was three times more effective than a continuous stream device.2 The pulsating action creates two zones of hydrokinetic activity (Figure 1):

- The impact zone—where the solution initially contacts in the mouth at the gingival margin

- The flushing zone—where the water or other irrigant reaches subgingivally

This hydrokinetic activity results in subgingival penetration and reduction of plaque biofilm.3 Subgingival access is beneficial because the plaque biofilm in this area contains a number of agents associated with inflammation and infection, such as gram-negative bacteria, endotoxins, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

A pulsating dental water jet allows for the regulation of pressure. Bhaskar et al4 showed that attached gingiva can withstand high amounts of pressure, up to 160 psi for up to 30 seconds, without producing irreversible damage. Moveable tissue is more vulnerable. From this, it was concluded that up to 90 psi is acceptable on undamaged oral tissue, while 50 psi to 70 psi is recommended for inflamed or ulcerated tissue.1 Selting et al2 found that efficacy was similar between medium- and high-pressure settings, but at lower settings, efficacy was less than 50%. These findings are in agreement with a position paper of the American Academy of Periodontology, which stated that “irrigation of 80 psi to 90 psi generally can be tolerated without untoward effects.”5

Effect on Biofilm and Bacteria

In 2001 the American Academy of Periodontology stated, “Among individuals who do not perform excellent oral hygiene, supragingival irrigation with or without medicaments is capable of reducing gingival inflammation beyond that normally achieved by toothbrushing alone. This effect is likely due to the flushing out of subgingival bacteria.”6 A number of researchers have found that a dental water jet reduces the amount of bacteria in the gingival crevice. Cobb et al3 and Drisko et al7 found that bacterial counts were reduced up to 6 mm. Cobb found that pulsed water irrigation also affected bacterial viability and the bacteria remaining in the pockets had a disrupted cell wall and reduced cytoplasm. These are referred to as “ghost cells” because they are nonfunctioning or dead (Figure 2A through Figure 2C).

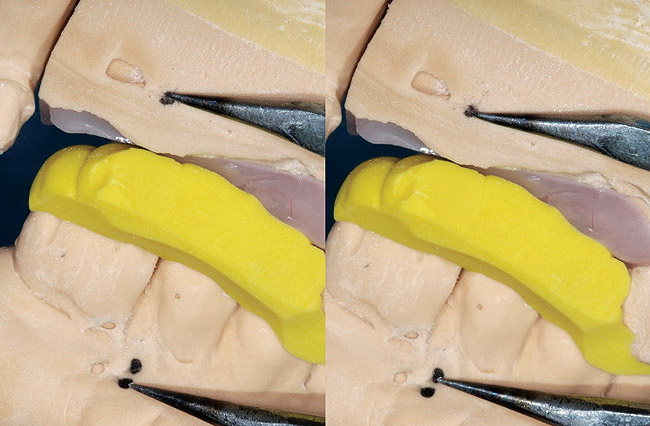

A recent in vitro study evaluated the effect of a standard and orthodontic dental water jet tip on plaque biofilm8 (see Gorur et al, pp 1-6). Ex-vivo plaque biofilm was grown on teeth extracted from a patient with advanced aggressive periodontitis. Tooth samples were treated with water, using either the standard jet tip or the orthodontic jet tip for 3 seconds at a medium-pressure setting. The samples were evaluated via scanning electron microscopy. Comparisons between the treated areas of the tooth sample and the untreated samples (control) revealed a 99.9% removal of salivary plaque biofilm by the standard jet tip and 99.8% by the orthodontic tip. The orthodontic tip also demonstrated significant removal of calcified in vivo-grown plaque biofilm.

Anti-inflammatory Effects

Several studies have shown that the dental water jet significantly reduces inflammation.9-12 Chaves et al9 found that the dental water jet significantly reduced inflammation even in sites with good plaque biofilm control. This result led Chavez to hypothesize that the dental water jet works by a mechanism independent of plaque biofilm removal and may involve specific host–microbial alterations in the subgingival environment.

Other studies confirm that bacterial cells exposed to pulsed irrigation produced less tissue-based mediators of inflammation. Al-Mubarak et al11 showed that patients who used twice-daily irrigation had significantly better reductions in serum measures of interleukin-1-beta (IL-1b‚) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) at 12 weeks. Cutler et al12 showed that daily water irrigation significantly reduced gingival crevicular levels of the proinflammatory mediators IL-1b‚ and PGE2 associated with attachment and alveolar bone loss.

Depth of Delivery

Studies have evaluated the depth of delivery into a periodontal pocket by a dental water jet. Boyd et al13 found that using the supragingivally placed tip (Standard Jet Tip, Water Pik, Inc, Fort Collins, CO) placed at the gingival margin allowed penetration of a solution to 54% of the depth of a pocket. An earlier study showed that a standard jet tip placed at 45° or 90° at 70 psi achieved penetration of solutions up to 71% in shallow (0 mm to 3 mm) pockets, 44% in moderate (4 mm to 7 mm) pockets, and 68% in deep (> 7 mm) pockets. Also, depth of penetration was found to be 75% or greater in 60% of deep sites.14 Statistically, tip angulation did not influence penetration.

Using a subgingival irrigation tip (Pik Pocket® tip, Water Pik, Inc), it has been shown that a solution reached 90% of the depth in pockets > 6 mm.15 In comparison, rinsing the mouth for 30 seconds reached 21% of the depth of the pockets (Figure 3). These depths of penetration studies help to explain why the dental water jet has been shown to be of benefit in patients with gingivitis and periodontitis.

Rationale for Patient Use

The rationale for having patients use a dental water jet is based on a number of studies. A dental water jet has been found to be significantly effective in reducing gingivitis, bleeding on probing, and plaque biofilm (Table 1).9-12,16-27 In many cases, these outcomes were achieved above and beyond routine oral hygiene, including flossing.10-12,16 In a 2005 position paper, the American Academy of Periodontology stated that “supragingival lavage can assist individuals with gingivitis or poor oral hygiene. The greatest benefit is seen in patients who perform inadequate interproximal cleansing.”6 The validity of this statement was demonstrated in a recent study. A dental water jet was paired with a manual or a power toothbrush and both were compared with traditional manual brushing and flossing to see which regimen was the most effective.10 The addition of a dental water jet, once daily with plain water, to either a manual or power brushing routine was an effective alternative to dental floss for the reduction of bleeding, gingivitis, and plaque biofilm. It is likely that many patients currently using a power toothbrush may get further improvements in oral health by the addition of a dental water jet.

Dental Water Jet Devices

Most of the evidence to support the efficacy of the dental water jet has been generated from investigations using the Waterpik dental water jet (Water Pik, Inc) (Table 2). A study of a device using a tip that incorporates microbubbles (Oral-B® OxyJet, Procter and Gamble Co, Cincinnati, OH) found that the observed effects were significantly different from their baseline scores, but there was no difference compared with regular oral hygiene regimens.28 Studies also have been published using a magnetized dental water jet (Hydro Floss®, Oral Care Technologies, Inc, Bessemer, AL).29,30 The device’s efficacy was evaluated on the lower anterior teeth in two studies. The index used to measure tooth accretions did not separate calculus from plaque and is not used in the literature as a standard method of measuring plaque and calculus. The “Accretion Index” has been used only in these studies. The index showed a statistically significant reduction of “accretions” on the lower anterior teeth compared with controls.29 The dropout rate of subjects who participated in one study was 24%, which far exceeds the 10% to 14% rate found in most 3-month studies and resulted in only 20 subjects who used the test device. The control irrigator in these studies was the same unit without the magnet.

Other studies suggest that reduction in calculus of 40% or greater can be accomplished with an irrigator without “magnetized” water. Lobene19 used a published calculus index and found a 50% reduction in calculus with a non-magnetized dental water jet (Waterpik dental water jet) compared with control. Felo20 found a 42% reduction with a non-magnetized device when delivering 0.06% chlorhexidine compared with a 22% increase in the 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse group.

Irrigation with Chemical Agents

Most dental water jets are designed so that commercially available mouthrinses can be used without causing any harm to the device mechanism. The chemical agents that have been shown to be the most effective are chlorhexidine and essential oils. Chlorhexidine (CHX) has been evaluated frequently in dental water jet studies (Table 1).

One of the benefits of using CHX is better interproximal and subgingival penetration compared with rinsing. Also, diluting CHX is acceptable for use in a dental water jet. Dilutions of 0.04% and 0.06% (based on a 0.12% concentration) have been shown to be effective via randomized clinical trials.9,17,21,22 Essential oils also have been studied as irrigants. Their efficacy has been demonstrated using the rinses at full strength.23,25 The efficacy of diluting these agents has not been studied.

Research with Special Populations

Orthodontic Patients

Orthodontic appliances present significant challenges for plaque biofilm control. A number of studies have evaluated use of the dental water jet in patients with orthodontic appliances. The studies demonstrated a significantly better reduction in plaque biofilm and inflammation compared with controls.27,31,32

A recent study compared the effect of a dental water jet with a special orthodontic jet tip with floss on plaque biofilm and bleeding in adolescent patients with fixed orthodontic appliances.26 Patients were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: (1) once-daily irrigation plus use of a manual toothbrush; (2) once-daily flossing plus a manual toothbrush; or (3) use of a manual toothbrush only. Patients assigned to the flossing and irrigation groups had to demonstrate proficiency with the use of a floss threader or the dental water jet. At 4 weeks, the dental water jet group exhibited 3.76 times the reduction of the floss group and 5.83 times the reduction of the brush group for plaque biofilm removal. The dental water jet group showed an 84.5% reduction in bleeding from baseline, which was 26% better than the reduction demonstrated by brushing and flossing.

Diabetes

There are more than 20 million people living with diabetes in the United States and 246 million worldwide. Because patients with diabetes have an increased risk for periodontal diseases compared with patients without diabetes, effective biofilm control is essential for them. Al-Mubarak et al11 looked at the effect of a dental water jet on individuals with diabetes. They found that, in addition to reducing the traditional clinical parameters of plaque biofilm, gingivitis, and bleeding on probing, twice-daily use of the dental water jet with a specialized subgingival delivery tip significantly reduced the expression of two destructive inflammatory mediators, IL-1β‚ and PGE2, better than routine oral hygiene regimens.

Periodontal Maintenance

A dental water jet with water added to the daily routine of patients in periodontal maintenance programs had significantly better reductions in gingival inflammation, bleeding on probing, and probing depth reduction compared with routine oral hygiene regimens.16,18 Likewise, studies that have used scaling and root planing followed by daily use of the dental water jet have also found better reductions in inflammation.21,25 Patients with periodontal diseases or who have completed periodontal therapy may especially benefit from use of a dental water jet as an adjunct to regular oral hygiene.

Implants

A study by Felo et al20 found that a specialized subgingival delivery tip (Pik Pocket tip, Water Pik, Inc) was both safe and effective for controlling bleeding and inflammation around implants. When a dental water jet using 0.06% (half-strength) CHX was compared with rinsing with 0.12% (full-strength) CHX, significant reductions strongly in favor of the dental water jet were observed. This study demonstrated that irrigation with 0.06% CHX was 87% more effective at reducing bleeding than rinsing with 0.12% CHX.20

Safety

Safety is as important as efficacy in recommending use of a product or device to a patient. Early studies confirmed the safety of the Waterpik dental water jet. Over time, the compilation of evidence from the more than 50 studies in more than 2,000 patients provides a well-documented profile on the safety of this dental water jet for most patients with daily use. In all of these studies, no significant adverse events have been observed by researchers or reported by patients.

Transient bacteremia is common in dentistry with the manipulation of the oral tissue and teeth. The 2007 American Heart Association guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis states, “Transient bacteria also occurs frequently during routine daily activities unrelated to a dental procedure, such as tooth brushing and flossing (20% to 68%), use of wooden toothpicks (20% to 40%), use of water irrigation devices (7% to 50%), and chewing food (7% to 51%).”33 The evidence supports the need to maintain good oral hygiene with the goal to eradicate dental disease to decrease the frequency of bacteremia from routine daily activities.

Compliance

Compliance is a major consideration when recommending any self-care device. Compliance has been evaluated in a few studies, with good compliance being reported. For example, a 6-month study by Flemmig et al17 found a 91.5% compliance rate with the dental water jet. In another study, Lainson et al34 followed up with subjects 1 year after the completion of participation in an oral irrigation study. They found two thirds of the patients still were using the dental water jet. Importantly, those using the dental water jet had significant reductions in gingivitis compared with those who stopped using one.

Conclusion

In view of the emerging data suggesting the important role of inflammation not only on periodontal diseases but also on the oral-systemic connection, the benefits of using the dental water jet may go beyond that of managing periodontal diseases, not only by reducing inflammation but also by affecting proinflammatory cytokines, which can affect the activities of a variety of body organs. The dental water jet is a safe and effective evidence-based device for improving and maintaining oral health in a wide variety of patient populations and oral health conditions. It is cost-effective, easy to use and, when used with water and paired with either a manual or powered toothbrush, has demonstrated clinical outcomes that are desired by both patients and practitioners. Finally, the dental water jet is an effective alternative to dental floss for those individuals who will not or cannot floss, providing significant reductions in bleeding, gingivitis, and plaque biofilm. Manufacturers’ specifications, especially for pressure and pulsation setting, are not equivalent. Dental water jets need to be evaluated separately, based on research specific to each product.

Disclosure

The author has received an honorarium from Water Pik, Inc.

References

1. Bhaskar SN, Cutright DE, Gross A, et al. Water jet devices in dental practice. J Periodontol. 1971;42(10):658-664.

2. Selting WJ, Bhaskar SN, Mueller RP. Water jet direction and periodontal pocket debridement. J Periodontol.1972;43(9):569-572.

3. Cobb CM, Rodgers RL, Killoy WJ. Ultrastructural examination of human periodontal pockets following the use of an oral irrigation device in vivo. J Periodontol. 1988;59(3):155-163.

4. Bhaskar S. Cutright DE, Frisch J. Effect of high pressure water jet on oral mucosa of varied density. J Periodontol.1969;40(10):593-598.

5. Greenstein G, Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: the role of supra- and subgingival irrigation in the treatment of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11):2015-2027.

6. Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Treatment of plaque-induced gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, and other clinical conditions. J Periodontol. 2001;72(12):1790-1800.

7. Drisko CL, White CL, Killoy WJ, et al. Comparison of dark-field microscopy and a flagella stain for monitoring the effect of a Water Pik on bacterial motility. J Periodontol. 1987;58(6):381-386.

8. Gorur A, Lyle DM, Schaudinn C, et al. Biofilm removal with a dental water jet. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;30(Suppl 1):1-6.

9. Chaves ES, Kornman KS, Manwell MA, et al. Mechanism of irrigation effects on gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65(11):1016-1021.

10. Barnes CM, Russell CM, Reinhardt RA, et al. Comparison of irrigation to floss as an adjunct to tooth brushing: effect on bleeding, gingivitis and supragingival plaque. J Clin Dent. 2005;16(3):71-77.

11. Al-Mubarak S, Ciancio S, Aljada A, et al. Comparative evaluation of adjunctive oral irrigation in diabetics. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(4):295-300.

12. Cutler CW, Stanford TW, Abraham C, et al. Clinical benefits of oral irrigation for periodontitis are related to reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27(2):134-143.

13. Boyd RL, Hollander BN, Eakle WS. Comparison of a subgingivally placed cannula oral irrigator tip with a supragingivally placed standard irrigator tip. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19(5):340-344.

14. Eakle WS, Ford C, Boyd RL. Depth of penetration into periodontal pockets with oral irrigation. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13(1):39-44.

15. Braun RE, Ciancio SG. Subgingival delivery by an oral irrigation device. J Periodontol. 1992;63(5):469-472.

16. Newman MG, Cattabriga M, Etienne D. Effectiveness of adjunctive irrigation in early periodontitis: multi-center evaluation. J Periodontol. 1994;65(3):224-229.

17. Flemmig TF, Newman MG, Doherty FM, et al. Supragingival irrigation with 0.06% chlorhexidine in naturally occurring gingivitis. I. 6 month clinical observations. J Periodontol. 1990:61(2):112-117.

18. Flemmig TF, Epp B, Funkenhauser Z, et al. Adjunctive supragingival irrigation with acetylsalicylic acid in periodontal supportive therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22(6):427-433.

19. Lobene RR. The effect of a pulsed water pressure cleansing device on oral health. J Periodontol. 1969;40(11):667-670.

20. Felo A, Shibly O, Ciancio SG, et al. Effects of subgingival chlorhexidine irrigation on peri-implant maintenance. Am J Dent. 1997;10(2):107-110.

21. Jolkovsky DL, Waki MY, Newman MG, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of subgingival and gingival marginal irrigation with chlorhexidine gluconate. J Periodontol. 1990;61(11):663-669.

22. Brownstein CN, Briggs SD, Schweitzer KL, et al. Irrigation with chlorhexidine to resolve naturally occurring gingivitis. A methodologic study. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17(8):588-593.

23. Ciancio SG, Mather ML, Zambon JJ, et al. Effect of chemotherapeutic agent delivered by an oral irrigation device on plaque, gingivitis, and subgingival microflora. J Periodontol. 1989;60(6): 310-315.

24. Walsh TF, Glenwright HD, Hull PS. Clinical effects of pulsed oral irrigation with 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate in patients with adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19(4):245-248.

25. Fine JB, Harper DS, Gordon JM, et al. Short-term microbiological and clinical effects of subgingival irrigation with an antimicrobial mouthrinse. J Periodontol. 1994;65(1):30-36.

26. Sharma NC, Lyle DM, Qaqish JG, et al. The effect of a dental water jet with orthodontic tip on plaque and bleeding in adolescent patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(4):565-571.

27. Burch JG, Lanese R, Ngan P. A two-month study of the effects of oral irrigation and automatic toothbrush use in adult orthodontic population with fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106(8):121-126.

28. Frascella JA, Fernández P, Gilbert RD, et al. A randomized, clinical evaluation of the safety and efficacy of a novel oral irrigator. Am J Dent. 2000;13(2):55-58.

29. Watt DL, Rosenfelder C, Sutton CD. The effect of oral irrigation with a magnetic water treatment device on plaque and calculus. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20(5):314-317.

30. Johnson KE, Sanders JJ, Gellin RG, et al. The effectiveness of a magnetized water oral irrigator (Hydro Floss) on plaque, calculus and gingival health. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(4):316-321.

31. Hurst JE, Madonia JV. The effect of an oral irrigating device on the oral hygiene of orthodontic patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970:81(3):678-682.

32. Phelps-Sandall BA, Oxford SJ. Effectiveness of oral hygiene techniques on plaque and gingivitis in patients placed in intermaxillary fixation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;56(5):487-490.

33. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guideline from The American Heart Association. Circulation [serial online]. April 19, 2007. Available at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095v1. Accessed Nov 25, 2008.

34. Lainson PA, Bergquist JJ, Fraleigh CM. A longitudinal study of pulsating water pressure cleansing devices. J Periodontol. 1972;43(7):444-446.