CBCT-Aided Multidisciplinary Approach to Salvaging an Intruded Tooth

Jaya Pamboo, MDS; Manoj Kumar Hans, MDS; Subhash Chander, MDS; Santosh Kumar, MDS; and Harleen Chinna, MDS

Abstract:

Among the most severe types of traumatic dental injuries is intrusive luxation, which displaces the affected tooth deeper into the alveolus, causing significant damage to the pulp and all of the supporting structures. This article describes a unique case of intrusive luxation of the mature left maxillary central incisor in an 18-year-old male patient. The diagnosis was confirmed using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), after which the intruded tooth was successfully repositioned by endodontic and orthodontic management. This was followed by prosthodontic rehabilitation. This case report also discusses the role of CBCT in effectively diagnosing this type of injury.

Traumatic intrusive luxation is one of the most severe types of dental injury that commonly affects maxillary incisors.1 Intrusion of a tooth refers to its displacement farther into alveolar bone. Intrusive luxation generally exists in 1.9% of traumatic injuries involving permanent teeth.2 Serious damage to the tooth pulp and supporting structures occurs because of the forced axial dislodgement of the tooth into its socket toward the alveolar bone. The repair process after intrusion can be complex.3 Intrusive luxation can lead to pulp necrosis, external/internal root resorption, loss of marginal bone support, replacement resorption/ankylosis, disturbance in continued root development, partial/total pulp canal obliteration, and gingival recession.4

The management of an intruded permanent tooth may consist of: (1) allowing spontaneous re-eruption; (2) surgical repositioning and fixation; (3) orthodontic repositioning; and (4) a combination of surgical and orthodontic therapy.3 Despite a variety of available treatment modalities, rehabilitation of intruded teeth is quite challenging. The present case report discusses the successful management of an intruded permanent maxillary left central incisor due to traumatic injury.

Case Report

Clinical Examination and Diagnosis

An 18-year-old male patient reported to the authors’ outpatient department following traumatic injury to his teeth caused by a fall during a fight 2 days earlier. Upon clinical examination, several problems were observed, including soft-tissue lacerations on his upper lip, intrusion of the maxillary left central incisor, and a complicated crown fracture involving pulp (Figure 1).There was no color change in the crown of the tooth, which was intact. The intruded teeth showed no mobility. There was no evidence of traumatic injury to any other teeth.

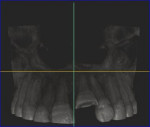

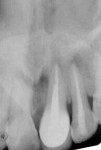

An intraoral periapical radiograph revealed an apically intruded maxillary left central incisor with closed apex (Figure 2). The cemento-enamel junction was located more apically—approximately 3 mm to 4 mm higher in the intruded tooth compared to the adjacent uninjured tooth. A multi-slice cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan (CS 9000, Carestream Dental, www.carestream.com) was performed on the involved tooth as well as the adjacent teeth to confirm the depth of intrusion (Figure 3). All required measures were taken to protect the patient from radiation, including the use of shielding devices such as a leaded thyroid collar for protection of the thyroid gland, leaded glasses to protect the eye lenses, and a leaded apron for protecting the body trunk.

The images were obtained in transverse, axial, and sagittal sections of 0.5-mm thickness. The scanning was done at a tube voltage of 96 Kv, a current of 12 mA, and exposure time of 12 seconds. CBCT scan slices confirmed 3 mm to 4 mm of intrusion of the maxillary left central incisor. The periodontal space surrounding the intruded incisor was diminished.5 There was no sign of external or internal root resorption.

At the initial appointment, the intraoral soft tissues were cleaned with saline and betadine. The patient was prescribed antibiotics, analgesics, and chlorhexidine mouthwash, and oral hygiene instructions were given and a soft diet was advised. Sutures were placed on the upper lip laceration.

Based on correlating clinical and radiographic findings, a complicated crown fracture involving pulp was diagnosed. The authors recommended root canal treatment of the intruded maxillary left central incisor, to be followed by orthodontic treatment. Informed consent from the patient was obtained after the treatment plan was explained.

Root Canal and Orthodontic Therapies

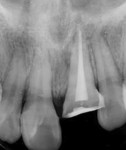

Root canal therapy was performed under rubber dam isolation using laterally condensed gutta-percha points (Tanari, Manacapuru, AM, Brazil, www.dentalcremer.com.br) and AH Plus® root canal sealer (DENTSPLY Maillefer, www.maillefer.com) in the maxillary left central incisor (Figure 4). The left central incisor was asymptomatic.

Orthodontic therapy was planned to reposition the luxated maxillary left central incisor after the endodontic treatment. It was performed using lingual splinting with traction on the intruded tooth for 6 weeks (Figure 5). The tooth was extruded approximately 0.5 mm every week and was thereby repositioned (Figure 6).

The maxillary left central incisor was further restored to improve esthetics using composite resin core build-up material (Vitremer™, 3M Dental Products, www.3m.com).

Prosthodontic Rehabilitation and Follow-up

After successful orthodontic treatment of the intruded tooth was completed, the tooth received prosthodontic rehabilitation. Following the post space preparation, a cast post was fabricated and cemented with resin-based cement (RelyX™, 3M Dental Products) for improved strength and stability (Figure 7). Finally, a porcelain-fused-to-metal crown was fabricated and placed on to the core and cemented (Figure 8).

The patient was recalled every 3 months for 1 year. Root canal treatment was performed on the maxillary left lateral incisor after it began showing signs of necrosis. A follow-up radiograph after 1 year showed no signs of progression of periapical pathosis (Figure 9).

Discussion

Intrusive luxations are serious traumatic injuries that often affect maxillary incisors, and the management of such cases can be complex. The treatment plan for these types of injuries depends heavily upon the severity of the injury.6 Treatment may range from a conservative approach, such as allowing for spontaneous re-eruption, to invasive methods involving immediate surgical repositioning. Spontaneous re-eruption is most common in intruded permanent incisors with immature root formation.3 According to the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSE), allowing for spontaneous re-eruption is especially the treatment of choice when the tooth apex is incomplete and/or the amount of intrusion is smaller than 3 mm, because the potential for eruption and pulpal or periodontal repair is high.7,8 This re-eruption is especially likely to occur when the dental pulp is vital; it rarely occurs when pulp necrosis is established.9

Thus, in the present case, due to the intrusion being more than 3 mm and because of pulpal necrosis, the multidisciplinary endodontic and orthodontic management was indicated. Orthodontic repositioning represents a biological procedure for teeth suffering these types of injury; moreover, an emergency endodontic treatment prevents inflammatory root resorption.8,10-12 It has been suggested that this alternative might allow for remodeling of bone and the periodontal apparatus. Successful treatment of cases using this technique has been reported in the literature.13 Andreasen and Andreasen have considered this option as the treatment of choice for most cases involving mature permanent teeth.13 The disadvantages of orthodontic extrusion have been reported as long treatment time and retention period, the need for strict patient compliance, and higher treatment costs.14-16

A cast post was advised in this case, as the maxillary left central incisor was labially inclined; therefore, to provide proper inclination of the prosthesis a cast post was fabricated prior to porcelain-fused-to-metal crown cementation.

CBCT was introduced in endodontics in 1990.17 This diagnostic imaging modality can greatly aid endodontic diagnosis. CBCT axial slices are a more helpful diagnostic tool than periapical radiographs, even if taken at different angles.18 CBCT also helps in identifying the root canal configuration—ie, whether the canals join together or run individually. Other applications of CBCT in endodontics include detecting dental and periapical pathosis, evaluating root fractures, and identifying internal and external root resorption. However, CBCT has inherent limitations such as high cost and increased radiation exposure compared to normal periapical radiographs; the effective radiation dose from CBCT is 0.6 mSv while it is 0.005 mSv using normal periapical radiographs.18

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of the possible need for a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of routine dental problems. This includes dental traumas that require comprehensive treatment and an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan that could involve surgeries, endodontics, orthodontics, periodontics, and prosthodontics. The investigational use of CBCT as a complementary imaging device helps in identifying these dental traumas, and the authors highly recommend it for use in endodontics.

About the Authors

Jaya Pamboo, MDS

Assistant Professor

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Institute of Dental Sciences

Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India

Manoj Kumar Hans, MDS

Professor

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

K.D. Dental College and Hospital

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India

Subhash Chander, MDS

Reader

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Vyas Dental College and Hospital

Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Santosh Kumar, MDS

Reader

Department of Orthodontics

Kothiwal Dental College and Research Centre

Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India</p>

Harleen Chinna, MDS

Assistant Professor

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Ryat Bahara Dental College and Hospital

Sahauran, Mohali, Punjab, India

References

1. Andreasen JO. Luxation of permanent teeth due to trauma. A clinical and radiographic follow-up study of 189 injured teeth. Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research. 1970;78(3):273-286.

2. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Matras RC, Andreasen FM. Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 1. An epidemiological study of 216 intruded permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22(2):83-89.

3. Humphrey JM, Kenny DJ, Barrett EJ. Clinical outcomes for permanent incisor luxations in a pediatric population. I. Intrusions. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19(5):266-273.

4. Sapir S, Mamber E, Slutzky-Goldberg I, Fuks AB. A novel multidisciplinary approach for the treatment of an intruded immature permanent incisor. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26(5):421-425.

5. Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28(1):2-12.

6. Wigen TI, Agnalt R, Jacobsen I. Intrusive luxation of permanent incisors in Norwegians aged 6-17 years: a retrospective study of treatment and outcome. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24(6):612-618.

7. Bruszt P. Secondary eruption of teeth introduced into the maxilla by a blow. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1958;11(2):146-149.

8. Tronstad L, Trope M, Bank M, Barnett F. Surgical access for endodontic treatment of intruded teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2(2):75-78.

9. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Andreasen FM. Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 3. A clinical study of the effect of treatment variables such as treatment delay, method of repositioning, type of splint, length of splinting and antibiotics on 140 teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22(2):99-111.

10. Oulis C, Vadiakas G, Siskos G. Management of intrusive luxation injuries. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12(3):113-119.

11. Andreasen FM, Pedersen BV. Prognosis of luxated permanent teeth—the development of pulp necrosis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1985;1(6):207-220.

12. Caliskan MK, Cinsar A, Türkün M, Akkemik O. Delayed endodontic and orthodontic treatment of cross-bite occurring after luxuation injury in permanent incisor teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13(6):292-296.

13. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Skeie A, et al. Effect of treatment delay upon pulp and periodontal healing of traumatic dental injuries—a review article. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18(3):116-128.

14. Andreasen FM, Pedersen BV. Prognosis of luxated permanent teeth—the development of pulp necrosis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1985;1(6):207-220.

15. Oikarinen KS, Stoltze K, Andreasen JO. Influence of conventional forceps extraction and extraction with an extrusion instrument on cementoblast loss and external root resorption of replanted monkey incisors. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31(5):337-344.

16. Alacam A, Ucüncü N. Combined apexification and orthodontic intrusion of a traumatically extruded immature permanent incisor. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18(1):37-41.

17. Kalender WA, Seissler W, Klotz E, Vock P. Spiral volumetric CT with single-breath-hold technique, continuous transport, and continuous scanner rotation. Radiology. 1990;176(1):181-183.

18. Scarfe WC, Levin MD, Gane D, Farman AG. Use of cone beam computed tomography in endodontics. Int J Dent. 2009;2009:634567. doi:10.1155/2009/634567.