The Future of Laboratory Workflows

Technology is enabling new models of collaboration to navigate the waters of dentistry

Carol Brzozowski

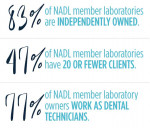

Emerging digital technologies for the communication of patient information and the design and fabrication of restorations are driving the future of laboratory collaboration. Furthermore, laboratory tools and workflows have evolved dramatically over the past two decades, and this has the dental laboratory industry grappling with a skilled labor shortage against the backdrop of consolidation. According to data from the National Association of Dental Laboratories (NADL), the number of dental laboratories with payrolls dropped from 7,715 in 2001 to 5,286 in early 2022, and the Commission on Dental Accreditation reported that the number of accredited dental technology programs in the United States dropped from 20 in 2010 to 13 in early 2022.1 Although improvements in scanners, design software applications, and mills have made the process of fabricating restorations in-office more accurate and predictable, 97% of the dentists who responded to an Inside Dentistry survey indicated they use a dental laboratory for crowns, bridges, dentures, and other needs. Moreover, 83% of the respondents indicated using more than one laboratory. Just 14% reported that they do some form of laboratory work in-office, such as milling, printing, or analog fabrication, and 5% reported that they employ an in-office laboratory technician. Despite the increasing accessibility of in-office fabrication methods, dental laboratories and their skilled technicians remain essential partners to dentists, whether it is for their knowledge of digital processes or the artistry of their techniques. The future of this partnership will be about enhancing collaboration to deliver even better outcomes for patients, but what will that collaboration look like?

"In the future, laboratory collaboration will continue to thrive via the use of digital technology," says Daniel Alter, MSc, MDT, CDT, the executive editor of Inside Dental Technology and a professor at the New York City College of Technology. "The collaborative approach to case evaluation, material selection, and treatment planning will expand even further, and the laboratory will engage in a significantly greater role as a restorative team member."

Today, laboratories can use technology to meet virtually with the patient and clinician, discuss material options, perform real-time evaluations with CAD software that incorporate the patient's face and scans of his or her teeth, and more. "In addition to earlier laboratory involvement in the treatment planning via videoconferencing and through software portals for sharing data, also key is laboratories' use of preoperative scans to produce digital mockups," says Alter. "With the skilled labor shortage, dentists need to ensure that they are aligned with laboratories that provide a sophisticated level of knowledge and acumen when functioning in a consultative role as well as when fabricating the final prosthesis."

Jason Olitsky, DMD, a private practitioner in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, who has an in-house laboratory, suggests that more dentists will handle at least some of their own laboratory work in the future, which will lead to reduced costs and greater efficiency when compared with hiring outside laboratories. "It may be some time before dentists are doing the majority of their own laboratory work because they tend to rely on knowledgeable, experienced technicians for complex cases," he says. "However, I believe that in the near future, the dentist will have greater involvement in the digital side of treatment planning and designing cases with some—but not all—of the indirect restorations being fabricated in-house." Regarding the restorations being fabricated by the laboratory, technology will be essential to enhancing collaboration. "Technology enhances efficiencies between dentists and technicians by providing digital workflows that are more user-friendly," says Olitsky. He notes that although many dentists heavily rely on technicians for material selection, esthetics, and occlusion, oftentimes, they do not give technicians enough information to succeed in these areas, and technology can help to improve that communication.

Keys to Success

Effective communication is critical to collaboration. In an Inside Dentistry survey, 32% of the respondents reported that they communicate face-to-face or by phone with the laboratory prior to delivery of the restorations on the majority of complex cases. In addition, 32% of the respondents indicated that they send full-face patient photographs to the laboratory for the majority of esthetic or complex cases. Josh Polansky, MDC, is the owner of Niche Dental Studio, a small high-end laboratory of 12 people in Voorhees, New Jersey. "Up to 90% of our dentists send full-face photographs, and 100% of the restorations are shown to the dentists before they leave the laboratory, which leads to better outcomes and less remakes," he says, adding that digital technologies also allow the patient to be part of the treatment plan.

Digital design software can be very helpful, but the fabrication of restorations still requires an operator with knowledge regarding function and material selection. "Technology is just a tool," says Alter. "To achieve successful outcomes, it must be coupled with a high level of knowledge of physiology, function, biomechanics, and material science." In addition, the development of natural esthetics requires an artistic touch. All of this can be achieved by collaborating with a laboratory that employs well-educated and experienced technicians.

When working with laboratories, dentists are looking to receive durable restorations and prostheses with quality esthetics and function as quickly as possible. "Due to pressure from patients to get cases finished and the desire to minimize issues with provisional restorations during the treatment phase, dentists almost always want their turnaround times to be as fast as possible," says Olitsky, "and for that to happen, the technician must have all of the necessary images and data to review."

"Whether the methods being used are analog or digital, the laboratory not receiving all of the proper data up front and in an organized fashion always holds up cases," Polansky notes. His laboratory has three Dropbox folders (ie, received, waiting on, and completed) to facilitate an efficient workflow between the technicians and dentists.

Regarding the laboratory technicians themselves, as digital fabrication methods are replacing analog ones, many dentists are prioritizing knowledge over artistry. "Quality esthetics and function can only be achieved by aligning with a well-versed dental laboratory technician who keeps abreast of all of the emerging innovations and materials," says Alter.

Polansky agrees. "In the analog world, dentists really wanted to find an artist or a creative technician," he says. "In today's world, dentists really want to be working with a very smart technician who has a lot of knowledge about dentistry—not just dental technology. Machines can do a lot of the artistic stuff. The more knowledgeable the operator, the better the outcome."

Considering patient safety is also critical to the success of laboratory collaboration. Approximately 88% of dentists who responded to an Inside Dentistry survey reported that they do not send any work overseas; however, most states do not require a laboratory to disclose where its work is being done or where its materials originate.2 Polansky believes that many laboratories that are claiming that their restorations are ‘made in America' are actually sending work overseas. "For some of these restorations to be made in America, the materials alone are going to cost more than they are charging," he says. "There are a lot of laboratories that are just middlemen switching boxes. They are American laboratories receiving scans, but they forward them along to overseas design facilities. Within a week, they're receiving a hard model back."

"I think clinicians quickly find out that outsourcing overseas is not predictable, can be inconsistent, and is oftentimes lacking in quality," says Alter. "It just is not a good business model."

Laboratory Workflow Models

There are many different models for the completion of laboratory work. The traditional approach involves sending all of the information for a case to a laboratory and receiving restorations that are ready to place. This approach is still the prevailing one, whether it includes the use of physical or digital impressions, and it is particularly appropriate for more complex cases that require more data capture and multiple verification steps to ensure appropriate restorative outcomes. Polansky started his career as a one-person dental laboratory, making everything by hand. "The transition from analog to digital wasn't always smooth," he says. "And although owning a lab in 2009 was different from owning a lab in 2023, the final product still needs to be beautiful. Dentists have become somewhat more demanding, but CAD/CAM has leveled the playing field."

Another model involves employing an in-house dental technician. That can offer a greater degree of control over the process; however, Alter notes that an in-house technician may not have the breadth of experience or access to innovations and materials that can be leveraged by working with a full-service outside dental laboratory.

A third approach is for dentists to do some or all of their own laboratory work in-house. This can involve outsourcing the design work to a laboratory and then fabricating the restorations in-house, doing the design work in-house and then outsourcing the fabrication to a laboratory, and other hybrid workflows, depending on the type of laboratory work that dentists are interested in doing. This model isn't for everyone. "A dentist's earning potential and expertise is best leveraged by seeing patients and providing them with best-in-class service, not doing the things that could be and should be delegated to a professional whose career is based on the work," Alter says.

Jeffry Tobon, CDT, is a laboratory technician who is merging his laboratory, Designlab Dental, with the Southeast Texas Implant Center. He is also the CEO of Chairside Solutions, a company that helps dentists build in-house laboratories. Tobon bases his business model on a philosophy that he developed in his homeland of Colombia, where dental technicians and dentists make equal pay. "What makes each one of us look good to the patient is what we can do in collaboration," he says. "You can be a great dentist, but maybe your laboratory is not delivering a good quality product with the esthetics desired by patients. Alternatively, the dentist may not be properly communicating what he or she needs to so that the laboratory can do what they need to do. Effective collaboration is essential." Tobon notes that there will always be a place for outside dental laboratories because not all dentists are up to the task of owning an in-house laboratory.

Olitsky, however, is a dentist who is definitely up to the task. "I am motivated by making things beautiful and being more hands-on in the restorative process," he says. "It is exciting to be able to design the teeth and make them in the office. As my workflow improved, it became more feasible for me to start building out our own in-office laboratory." Olitsky says his goal was to first get comfortable with exocad, then integrate it into various indirect fabrication processes in the office. Beyond his interest in design, Olitsky enjoys the hands-on aspect of laboratory work, and his practice benefits from decreased turnaround times and lower overhead. "Hiring additional team members to handle the increased workflow associated with in-house laboratory work frees up the dentist to tend to patient interaction when needed," he says. "When a practice adds an in-house laboratory, hiring an experienced technician can help to ensure quicker growth with less interruption in the quality of restorations."

Farhad Foroughi, DMD, owns a private practice in Bradenton, Florida, where restorations are designed by an outside laboratory and then milled in-house. "We started scanning and milling crowns in the office with CEREC®, doing all of the staining, glazing, and everything," he says. "We do our crowns the same day. We also scan for dentures, partial dentures, and night guards, which has been a lot more accurate."

Bill Atkission, co-owner and head technician at Bella Vita Dental Designs, Arden, North Carolina, handles the design functions for Foroughi's practice. Foroughi points out that although in-house laboratories can be beneficial to dental offices, having a laboratory technician in-house means having the volume to justify it. "The advantage of working with Bella Vita Dental Designs is that Atkission accommodates special requests, including emergency work," he says, adding that many laboratories don't work on demand. "It also frees me up to see more patients." Foroughi notes that in-office fabrication technology is only useful if it is used to maximum capacity and recommends that dentists making the investment take continuing education courses to produce a more superior product. "The rewards associated with fabricating restorations in-office and not having patients come back for a second visit are tremendous if you train your team and get really good at it," he says.

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) to design restorations offers another model. Although the technology has limitations, for simpler cases, such as single crowns, AI allows dentists who are not proficient in the use of design software to input the data that they usually send to the laboratory and receive a design to mill or print a restoration. "AI is amazing," says Foroughi, whose office has explored software that uses AI to read radiographs. "It picks up things that your eyes may have glanced over and missed, and it gathers and stores images from patients year to year for comparisons."

What's Best?

In addressing which model is the best choice for a dentist, Polansky notes that although many dentists would like to do at least some of their laboratory work in-house, it's important to understand that dental practice operations and dental laboratory operations are truly separate businesses. "Doing laboratory work necessitates understanding the costs of CAD software, milling units and 3D printers, and their upgrades; the need for customer service when the machines go down; and all of the specifics of operation, such as what psi the air compressor needs," he says. "You will need skilled labor and have to pay for it. There's a huge shortage of dental technicians right now, and hiring a good one can cost as much as hiring an associate dentist. Some dentists who have tried it find it to be too overwhelming and return to using an outside laboratory."

Ultimately, the expertise of a trained dental technician in some form will always be critical to the practice of dentistry. Even if dentists who like to design and fabricate their own restorations could do it all by themselves and remain profitable, they would lose the benefits that come from collaborating with a technician, whether he or she is in-house or working for an outside laboratory.

Chairside Solutions provides technician integration training. "We're starting an internship in Houston where technicians can stay for a week, work in the laboratory, and learn how to design and finish," Tobon says. "They learn to use the design software, milling software, 3D printing system—everything. For dental offices that are having a hard time hiring a qualified technician, sometimes it's best to offer training to someone who is already on staff."

"Although machines have gotten better at turning out restorations with less human interaction that protect the teeth, only an experienced and creative technician can interpret the information, be sparked with inspiration, and work with passion to create beauty for dentists and their patients," says Olitsky. "If dentists are capable of doing all of the laboratory work by themselves, they sacrifice the benefits of collaboration with technician partners who can offer guidance regarding esthetics, material selection, and occlusion to complete challenging cases."

Tobon hopes that dentists continue to see the value in partnering with dental technicians. "Ultimately, what really makes the dentist look good is the work of an excellent laboratory technician," he says. "If the restoration looks good, then the dentist does too. It would really benefit the industry to see more dental technicians partnering with dentists to start businesses together."

The Future Is Digital

According to Polansky, dentists should view their laboratory technicians as specialists, especially in today's digital world. "Dentists will talk with the endodontist, surgeon, and orthodontist, but for some reason, many dentists don't want to talk to the laboratory technician," he says. "The irony of that is that the technician's effort is the end of the restorative work—what the laboratory does is what is seen by the world."

Polansky emphasizes that dentistry hasn't really advanced that much from its beginnings. "Occlusion is still occlusion; it's an age-old philosophy," he says. "But the digital technology and workflows being used on the laboratory side have skyrocketed to the moon, and many dentists are no longer on the same page as their technicians." Ironically enough, Polansky has actually seen many laboratories outgrow their dentists who are still using all analog methods. "I've seen a lot of laboratories say to their dentists, ‘We can no longer work with you. We don't work the way that you work anymore, so working with you is becoming disruptive to our laboratory,'" he says. "We're at a point with our laboratory where we have doctors who are so old school that we've had to have conversations. We're trying to transition people over to the new world. But it's been a struggle."

Paradoxically, dentistry's evolution into digital processes appears to be the force that's driving some dentists to want to do their own laboratory work in-house as well as driving others to want to collaborate with more knowledgeable laboratory technicians. Regardless of whether dentists chose to collaborate with an outside laboratory to do all of their laboratory work, to do some of their own laboratory work and collaborate with an outside technician to do the rest, or to collaborate with an in-house laboratory technician that they employ, there's no doubt that in the future of dentistry, the language of collaboration will be digital.

References

1. Feldman-Harless H. Uplifting higher education: the state of the college system, how it is impacting the profession, and what those both within and outside it can do to help. Inside Dental Technology. 2022;13(5):6-17.

2. National Association of Dental Laboratories. State Regulation. What's In Your Mouth? Campaign website. https://dentallabs.org/state-regulation/. Accessed March 14, 2023.